This essay was written in conjunction with Marilyn Lerner: Harmonies, on view at CUE September 8 – October 15, 2016.

Figure 1. Marilyn Lerner, Pink, 2015-2016. Oil on wood. 40" x 26". Private collection.

When I met the painter Marilyn Lerner in her Chelsea studio on a sweltry June morning, I was impressed to learn that the small couch in the middle of the room was not there for sitting, as I had assumed, but was actually the place that the slight, curly-haired artist slept every night as she advanced her newest body of acutely colored, geometric abstractions. Knowing this, the short distance to her actual bedroom—located several yards away behind a freestanding partition—became more metaphorical than physical. The passage from the psychological realms of the work to her living quarters and back was apparently too great to make over and over again; as she traveled deeper into the latter, it was necessary to set up a bed there, rest, and wake with the work each day in order to move farther with it. Lerner’s obsessive immersion gives us the privilege of encountering paintings that have been created slowly, and with minimal outside influence, as opposed to the influx of external references so common in much “post-internet” painting of today.

The artist instead works surrounded only by her own headspace: her most recent series, begun over the past two years, is the result of spending long months in deep focus and solitude in the studio—as she has always done, but this time with greater deliberation than before. I learned that the paintings’ polychromy is completely unplanned, as she mixes each hue of oil in response to the colors and forms around it, creating a fully self-determined painting. The result is a singular work whose interior vibrations and spatial relationships are at first unexpected, but ultimately persuasive.

As in many of her previous geometric explorations, Lerner eschews academic color theory in favor of a logic that is based on the painting itself, seen best in Pink, 2016 (Figure 1). A warm magenta bolsters the center of the composition, with shades of pink reverberating around it, punctuated with staccato blocks of highly unexpected tones: forest green, slate grey, navy blue, and dark brown. The rectangle—repeated, reoriented, and broken up—is the unifying structure; its interlacing allows for Lerner’s individuated color vocabulary to follow its own logic. Here, the color spectrum is turned on its head and rearranged into a precise chaos within the confines of its dimensions that feels intensely deliberate in its aggregate wholeness.

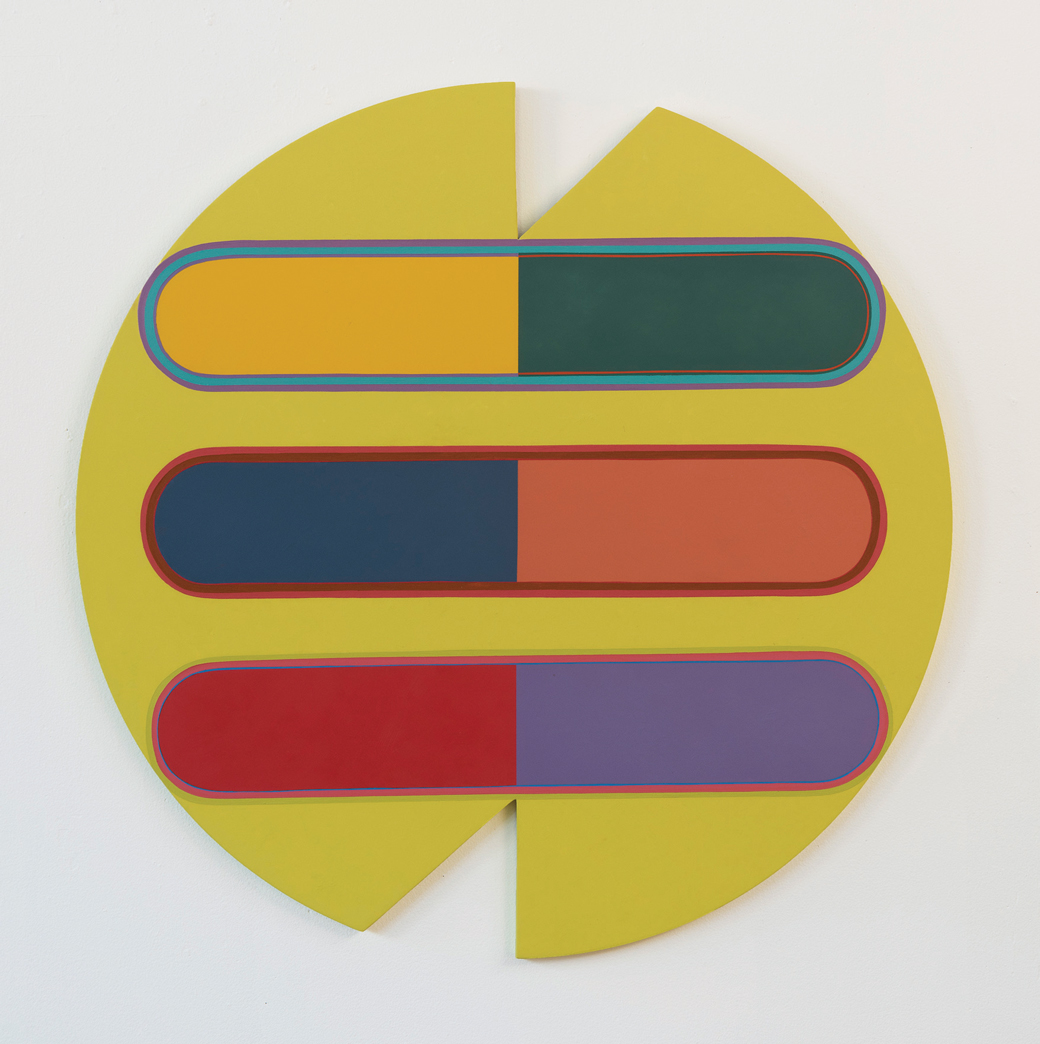

While most of Lerner’s syntactical shapes surface within the painting, for this new series, she began re-incorporating shaped supports—something she had abandoned in the early ’90s and picked back up—with What Goes Around Comes Around, 2016, (Figure 2). When she chooses the size and shape of her wood panels, it is as purely instinctive as her color system. According to Lerner, the incised circular shape of this particular panel dictates the forms within it, and the forms within determine the interaction of color: improvised movements flourish within a predetermined structure—not unlike many forms of music. As Lerner instructed me on our visit, “Music has the same wavelength as color.”

Figure 2. Marilyn Lerner, What Goes Around Comes Around, 2015-206. Oil on wood. 36” diameter circle.

In her artist statement, Lerner has herself expressed that she at one point aspired to make paintings that visually corresponded to the sound of Javanese Gamelan music (a sustained passion she pursued during multiple trips to Southeast Asia). It’s not hard to see how the elaborate rhythmic structures of Gamelan music, in which each instrument is set to its own tuning system, relate to the artist’s complicated visual systems and idiosyncratic geometric vocabulary. The influence behind these recent paintings is Algerian Raï folk music, whose soulful, impassioned longing appear to have inspired even further rapture in color and form. But while Lerner has certainly been influenced by the music and art of East Asia and Africa, the content of the paintings remains completely insular to the work.

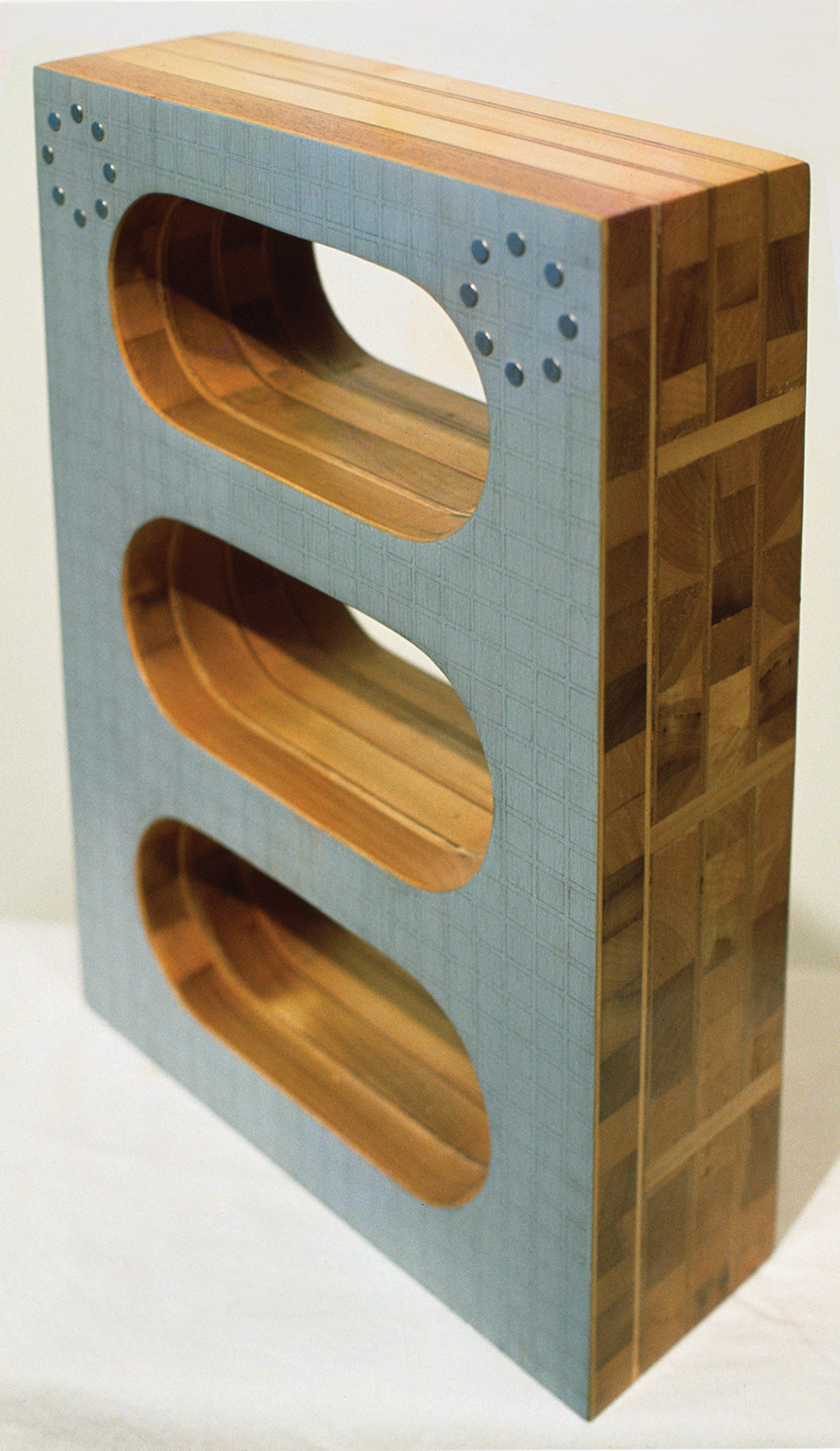

Though one would not expect so in looking at this series, Lerner did not start out as a painter. She began her initial course of study as a printmaker at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, around the time printmaker Alfred Sessler spearheaded a huge expansion of its printmaking program and teaching methods, spurring a print renaissance at the university. After earning her BFA, she moved to New York to pursue an MFA at the Pratt Institute, but rejected printmaking upon graduation. She found a tiny studio in SoHo and started making sculpture from the refuse of factories and industrial manufacturers that surrounded the neighborhood. The result of this period was extraordinary sculptures modeled from wooden die cut shapes, which were included in the 1970 Sculpture Annual at the Whitney Museum of American Art. They are fascinating not only for the cues she says she took from H.C. Westermann, but also for Lerner’s audacity in picking up power tools and metal clamps for the first time in order to teach herself the demanding techniques with which she wrought these impressively polished forms.

Figure 3. Marilyn Lerner, What Goes Around Comes Around, 1969. Laminated wood, acrylic paint, graphite pencil, and metal studs, 18” x 13” x 5”

But by 1970 Lerner had completely abandoned sculpture, taken up painting, and settled into her current studio in Chelsea. Her abiding interest in non-Western cultures—inspired by her early childhood fascination with anthropology—spurred her to embark on a series of serious travels throughout the ’70s and ’80s. She spent months alone, moving through Turkey, North Africa, and Southeast Asia at a time when and in places where women did not enjoy the same public freedoms they do today. And just as she fearlessly rode a motorcycle through the remote outer islands of Indonesia—alone, without a helmet or even a map—she started over in her art practice. With confident abandon, Lerner once again taught herself a new technique while remaining committed to the same considered building of forms.

The impetuous self-transformation from one medium to another seems to have freed the artist to develop the confident geometric language present in the newest paintings: the remnants from each new period have evolved to feed her ever-changing aesthetic system. Such artistic evolutions themselves are only possible given the depth that comes with focusing on one thing at a time. Perhaps Lerner’s restrained boldness is aided by her strict adherence to repetition and ritual. Each day in the studio begins and ends in the same exact manner; I observed an impeccably ordered workspace, with cleanly wrapped mixed color from previous sessions, ready to go. Her adjacent living space is decorated with Indian miniature paintings, textiles, ceramics, altars, and various objects collected from India, Bali, and China—her inspirations and materials neatly organized and close at hand.

Among her collection hangs a Jain painting with a circular mandala, a form that Lerner frequently references and often stands in for a microcosm—and is an apt metaphor for the artist’s process. According to Eastern religious traditions, such a form is inherently magical; its very existence is meant to affect and be affected by the space around it. But in her paintings, Lerner completely extricates it from its spiritual context, an act she ardently defends by articulating her own disinterest in religion. It’s a far different and deeper method than the appropriation of exotic forms, colors, or cultures. It is instead a subconscious processing of these stimuli, which is articulated years, and sometimes decades, later in the equally unplanned moment in which her brush touches the surface. Accordingly, these newest paintings float in a less accessible, unconscious realm in which the senses—especially sight and sound—are applied rigorously to synthesize new geometric and tonal vocabularies. This abstraction is not the means to an end but the end in itself.

What Goes Around Comes Around, 2016, exemplifies the spontaneous freeing of these eternal forms from their context and their quiet echoes within Lerner’s own oeuvre. For this new painting, the lozenge from her 1969 sculpture of the same name has been rearticulated in a field of punchy yellow, but the artist insisted to me that this was not a foregone conclusion when she approached the blank surface. Although they were selected in the moment, her color choices here (and elsewhere) exhibit a typically rigorous engagement with various inputs absorbed from her intensive travel experiences in Turkish markets, studies with master Indian painters, and at Indonesian festivals. The piece is thus at once unplanned and deliberate, suggesting that random chance finds its most authentic expression in the silent, still moments in Lerner’s studio—and offers us a sustained, spontaneous experience of our own, if we can simply look as slowly as the work urges us to.

This essay was written as part of the Young Art Critic Mentoring Program, a partnership between AICA-USA (US section of International Association of Art Critics) and CUE, which appoints established art critics to serve as mentors for emerging writers. In 2014, CUE joined forces with Art21, combining the Young Art Critic Mentoring Program with the Art21 Magazine Writer-in-Residence initiative. Each writer composes a long-form critical essay on one of CUE’s exhibiting artists for publication in CUE’s exhibition catalogue, which is also published by Art21 in its online magazine. Please visit aicausa.org for more information on AICA-USA, or cueartfoundation.org to learn how to participate in this program. Any quotes are from interviews with the author unless otherwise specified. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior consent from the author. Lilly Wei is AICA’s Coordinator for the program this season. For additional arts-related writing, please visit on-verge.org.

Writer Anna Tome is a Brooklyn based writer, researcher, and curatorial assistant. Her work has appeared in Hyperallergic, the Brooklyn Rail, C Magazine, and elsewhere. She received a BA in English Literature and a BA with honors in Art History from Mills College in 2010. She is currently an MA candidate at Hunter College.

Mentor Sarah P. Hanson writes about art, design, and culture for New York, T, Modern Painters, Artinfo, and Artnet News, among others. A former editor in chief of Art + Auction magazine, she holds a B.A. from Vassar College and has also served in editorial roles at ARTnews magazine, Assouline Publishing, and Paddle8.