This essay was produced in conjunction with the exhibition Wendy Red Star: Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise," curated by Michelle Grabner, on view at CUE Art Foundation, June 1–July 13, 2017. This text is included in the free exhibition catalogue available at CUE.

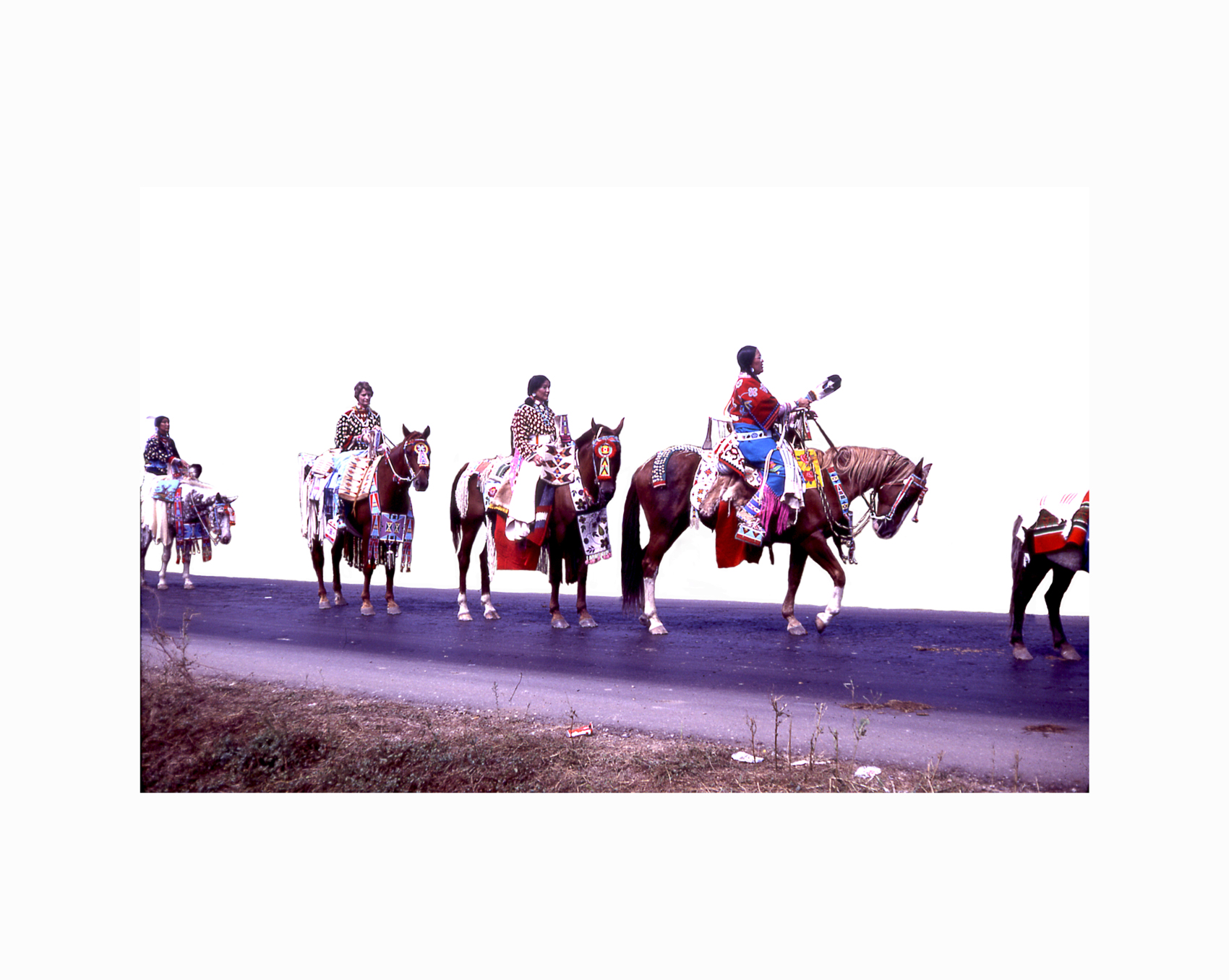

Wendy Red Star, Yakima Nation Youth Activities, 2014, slide of Crow Fair parade at Crow Agency in the 1970s, archival pigment print.

In 1851, Chief Sits in the Middle of the Land negotiated with the United States to define the territory of the Apsáalooke (Crow). He stated his aspirations for the future of his people, proclaiming: “Where my four base teepee poles touch the ground, will be my land.”[1] As an undergraduate at Montana State University located in Bozeman, Wendy Red Star’s research found that this treaty had included Bozeman, and by extension all the land held by the university[2]. In response to this history Red Star erected a traveling installation of lodge pole teepees across the campus, disrupting common walking paths and briefly occupying the football field. It was the beginning of a practice that utilizes brash humor, scholarly research, and personal narratives to hold space in a postcolonial world, often reworking clichéd imagery of Native Americans to satirical effect.

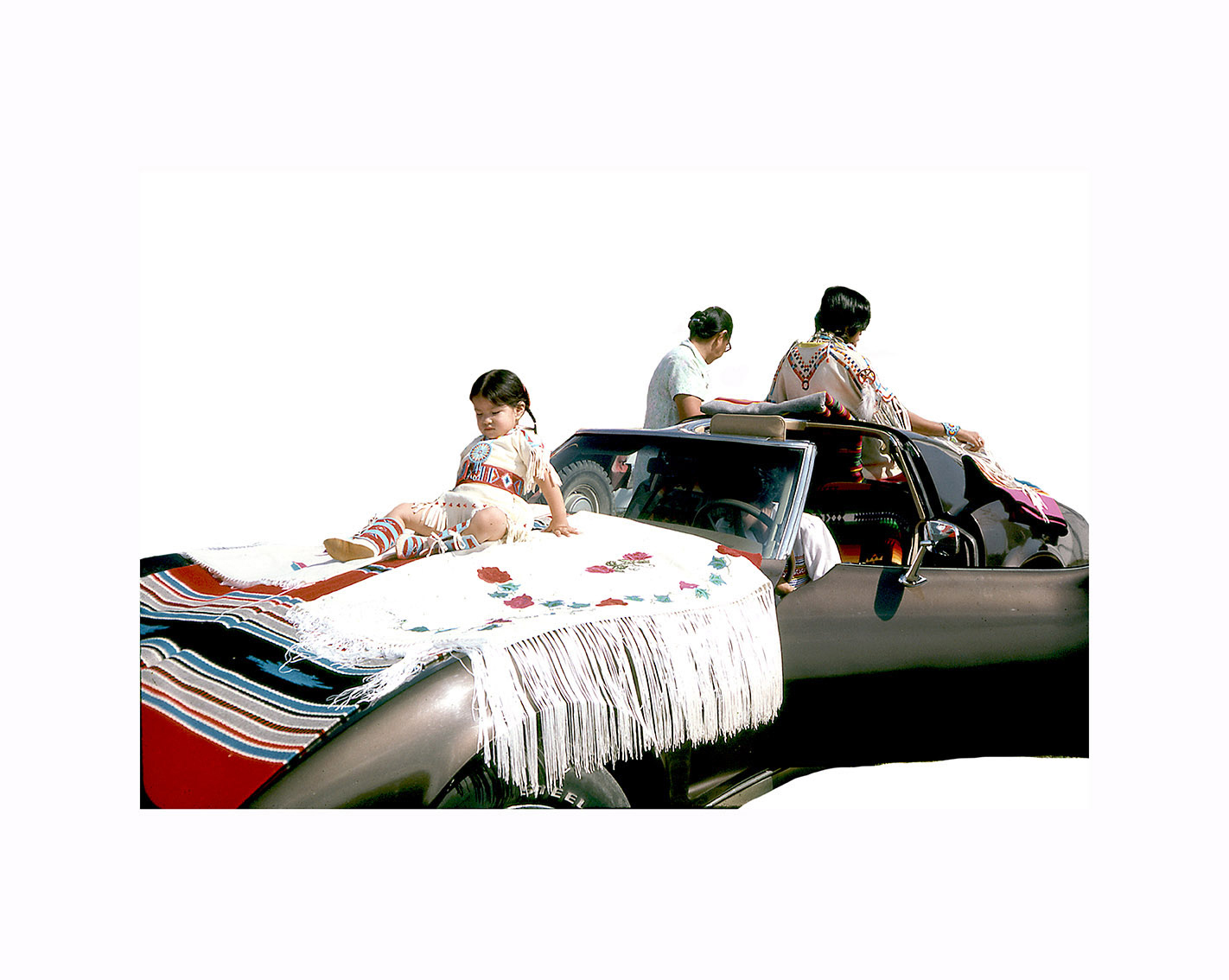

For Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise,” Red Star’s first solo exhibition in New York, the artist eschews much of the satire of her earlier work, showing a large-scale installation drawn from a mix of autobiographical and archived material. Using found and personal photographs taken from the annual Crow Fair in Montana, the work is installed to create a sense of motion, a “parade” of cars, floats, and horses dressed in blankets and beadwork, ridden by participants in elaborate Crow regalia. Arranged chronologically from the early 1900s to the present day, the work functions as a historical timeline of one of the largest Native American gatherings in the country as well as a celebration of a creative practice that has been largely overlooked by prevailing historical accounts.

Even in her most sardonic works, Red Star has consistently invited audiences to interact with and consider cultural productions and viewpoints outside of dominant colonial narratives. Her work acknowledges the public’s ongoing interest in the Native American experience (both real and imagined), and while it often offers sharp criticism of the racist functions of Native representation, her work also gives viewers an opportunity to experience the perspective of a contemporary Crow artist researching and processing her identity and history. The exhibition Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise” invites audiences to witness an important and long-standing cultural tradition, and to see the annual Crow Fair filtered through Red Star’s personal relationship to the event.

Red Star herself grew up on the reservation where the fair is held and has participated in the festivities with her family for her whole life. The photographs, video, and memorabilia of the exhibition represent traditions that she continues to pass down to her daughter, Beatrice, with whom she attends the event annually.

Much of Red Star’s earlier work addresses the relationship between depictions of the Native experience within popular culture and the lived experience of contemporary Native Americans, taking on themes of exoticism and sexualized stereotypes. In Four Seasons (2006), Red Star poses in a series of four photographs in an elk-tooth dress, which is a traditional Crow garment.[3] Each portrait is set against a backdrop depicting a season, and is constructed of synthetic materials such as AstroTurf, inflatables, and 1970s scenic landscapes. The images evoke both the dioramas of a natural history museum and romanticized western paintings. In White Squaw (2013), Red Star poses for the covers of E.J. Hunter’s 1980s paperback novels. One image, in which she licks a hatchet, is captioned by the cover text that reads “Hard pressed for revenge she knows all the right moves!”

While these works can be seen both as a reclamation of Native identity and a critique of tired and exploitative social narratives, Red Star’s practice also delves into the deeply personal. In her series Family Portraits (2011), she creates photo collages that combine family photos with saturated textile quilting patterns, evoking the rich connection between traditional Crow designs and familial ties. Images of HUD houses, rez cars, horses, and powwow regalia regularly appear in her work—an aesthetic that calls back to a childhood spent on the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana. The imagery of Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise” similarly draws on Red Star’s lived experience.

The history of the Crow Fair begins in 1904. In an attempt to incentivize self-sufficiency through farming, S. C. Reynolds, the local “Indian Agent” appointed by the U.S. Government to enforce federal regulations, created a festival he imagined would be much like a Midwestern county fair, with cash prizes given out for handicrafts, processed foods, and produce grown by reservation residents.[4] In hopes of encouraging attendance, he also lifted the U.S. Government’s restrictions on traditional Indian ceremonies and gatherings. This was a significant departure from the “Code of Indian Offences,” which outlawed feasts, dances, and other aspects of indigenous culture.[5] It was this opportunity to socialize and reaffirm a unique cultural identity that gave the fair its staying power.

Since its origin, the Crow Fair has expanded and evolved into a six-day event, held on the third week of August. The banks of the Little Bighorn River become known as the “The Tepee Capital of the World,” as approximately 1,500 teepees are erected around a 200-foot dance arena. A parade of horses, trucks, cars, and floats covered in intricate beadwork and blankets kicks off the occasion, followed by an all Indian rodeo, horse races, and dance competitions. Today, the fair attracts around forty-five thousand attendees.[6]

For Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise, Red Star works with photographs from the Crow Fair, creating cut outs that isolate figures, highlighting the details of the participants, their horses and vehicles. Some of the images come from the artist’s research, some are personal, some are provided by family members. The isolation of the fair attendees from their original backgrounds leaves the viewer to focus on the exquisite details of Crow artistry: the fringe of one rider’s sleeve, bead work, blankets covered in geometric patterns, the intriguing way horses and cars are adorned similarly, women in elk tooth dresses, and men wearing feather back bustles and breast plates.

More than a historical study, Red Star’s project weaves a story of survival and ultimately a riotous celebration of a culture that has pushed back against marginalization. Red Star offers an alternative lens to view Crow Fair images, and a very real reminder that this cultural production is continuing to evolve. While so many dominant narratives are busily flattening Native identities and culture, Red Star is working to expand, personalize, and humanize through asserting her own particular perspective.

This focus places Red Star in conversation with other artists who work directly with themes of identity, particularly those who came into prominence in the late 1980s and early 1990s under a barrage of social pressures related to race, gender, and religion. In 1992, Fred Wilson’s landmark project “Mining the Museum” used the Maryland Historical Society to bring to light unspoken inequalities in the way museums build and display their collections. Shirin Neshat’s 1993 photographic series Unveiling examined women in a shifting Middle East, and, in 1994, Kara Walker debuted her first large scale silhouette work Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. As Jerry Saltz wrote, not only did this turn disrupt the long held separation of artwork and the “self,” but also called into question “the way culture is formed, how art is made—and what counts as art.”[7] What, then, does it mean for Red Star to deploy these tools today, nearly twenty-five years later?

Working within a political landscape that has seen a return of many of the same tensions and conflicts that defined the culture wars, Red Star builds upon the tactics taken up by artists like Wilson, while also leveraging a new landscape of social media and image distribution. By gathering together documentation, ephemera, and written records relating to Crow Fair, Um-basax-bilua “Where They Make The Noise” reinforces two interconnected truths: that American history does not start with European settlement, and that indigenous history doesn’t end with it. Rather the two histories are one and the same.

As Red Star states, “We need to be treated as human beings. Our history is everybody's history, it's not a segregated history.”[8]

[1] Crow Tribe of Indians, “Crow Natural, Socio-Economic and Cultural Resources Assessment and Conditions Report,” Bureau of Land Management, April 15, 2002. Accessed March 11, 2017.

[2] In 1851, the Apsáalooke territory covered much of present-day Montana and Wyoming. In 1868, a reservation was established covering a fraction of that territory, completely within present-day Montana.

[3] Luella N. Brien, “Wendy Red Star on the Rise,” Native Peoples Magazine, November-December, 2014.

[4] Matt Hoffman, “Teepees, powwows, Native culture front and center at Crow Fair,” The Billings Gazette, April 8, 2016.

[5] Stephen Fadden and Stephen Wall, “Invisible Forces of Change: United States Indian Policy and American Indian Art,” in Manifestations: New Native Art Criticism, ed. Nancy Mithlo (Santa Fe: Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, 2011).

[6] Maria Scandale. “93rd Annual Crow Fair Celebration Under the Big Sky,” Indian Country Media Network, August 18, 2011. Accessed March 11, 2017.

[7] Jerry Saltz and Rachel Corbett, “The Reviled Identity Politics Show That Forever Changed Art,” Vulture, April 21, 2016.

[8] Braudie Blais-Billie, “Wendy Red Star Makes Probing Art About Native American Identity” I-D, November 18, 2016.

---

This essay was written as part of the Art Critic Mentoring Program, a partnership between AICA-USA (US section of International Association of Art Critics) and CUE, which pairs emerging writers with AICA-USA mentors to produce original essays on a specific exhibiting artist. Please visit aicausa.org for more information on AICA-USA, or cueartfoundation.org to learn how to participate in this program. Any quotes are from interviews with the author unless otherwise specified. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior consent from the author. Lilly Wei is AICA’s Coordinator for the program this season.

Josephine Zarkovich is an arts writer and curator based in Oregon. She received an MA in Curatorial Practice from California College of the Arts and is editorial director of 60 Inch Center, an art criticism website. Her curatorial work focuses on engaging audiences and fostering critical discussions around popular culture. She currently serves as the curator of the Linfeld Gallery in McMinnville and is co-director of the Portland ‘Pataphysical Society, an alternative arts space located in Portland’s Everett Station Lofts.

Mentor Sara Reisman is the Artistic Director of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, whose mission

is focused on art and social justice in New York City. Recently curated exhibitions for the foundation include Mobility and Its Discontents, Between History and the Body, and When Artists Speak Truth, all three presented on The 8th Floor. From 2008 until 2014, Reisman was the director of New York City’s Percent for Art program where she managed more than 100 permanent public art commissions for city funded architectural projects, including artworks by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Mary Mattingly, Tattfoo Tan, and Ohad Meromi, among others for civic sites like libraries, public schools, correctional facilities, streetscapes and parks. She was the 2011 critic-in-residence at Art Omi, and a 2013 Marica Vilcek Curatorial Fellow, awarded by the Foundation for a Civil Society.