This essay was written in conjunction with Tamara Johnson: No Your Boundaries, on view at CUE February 13 – March 23, 2016.

Whatever it is, it avails not—distance avails not, and place avails not,

I too lived, Brooklyn of ample hills was mine,

I too walk’d the streets of Manhattan island, and bathed in the waters around it,

I too felt the curious abrupt questionings stir within me,

In the day among crowds of people sometimes they came upon me,

In my walks home late at night or as I lay in my bed they came upon me,

I too had been struck from the float forever held in solution,

I too had receiv’d identity by my body,

That I was I knew was of my body, and what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

As a child growing up in Waco, Texas, Tamara Johnson moved between the private art classes in which her mother enrolled her—and to which she sported a beret—and the warehouse out of which her father ran a granite and tile company. “It was like his studio,” she explained in a late fall studio visit. “I hated going there, but I grew up like that. You have tools and you build stuff.” Some of Johnson’s anecdotes about her childhood in Waco evoke a carefree American idyll, though one memory that stands out is the 1993 FBI siege of the Branch Davidian cult’s headquarters just outside her hometown, which left 80 people dead. An underlying anxiety about place permeates Johnson’s practice as a sculptor.

If the challenge is to situate oneself within one’s present, the tools Johnson uses to do so are rope, silicon, paint and wood. It’s not hard to imagine that the time she spent staving off boredom at the granite warehouse has contributed to her becoming a sculptor: It is through building objects, and parsing their material qualities and the significance of their existence, that Johnson negotiates her own space within the world. Based in New York City for the past three years, following undergraduate studies at University of Texas at Austin, three years in Texas and then an MFA at Rhode Island School of Design, Johnson is driven by an interest in the interplay between ideas of familiarity/unfamiliarity and interior/exterior and how they are experienced personally, as well as on a larger social scale.

Whereas Marcel Duchamp ascribed the title of “art” to common objects, and Claes Oldenburg re-created common objects at large scale, Johnson re-creates common objects and then places them within unfamiliar contexts. Take, for instance, her garden hoses. Familiar to all suburban Americans, they become foreign fossils when placed within an urban white-cube gallery. While the hoses appear malleable, like Oldenburg’s soft sculptures, in reality they are fixed, frozen by internal metal armatures, as if time was paused while the hose was transported 2,000 miles from the Waco backyard where it belongs. In a late fall studio visit, Johnson described adjusting to life in New York City—a place vastly distant from her Texas home—as adjusting to a “loss of function.” It is a sensation expressed in her work. “This idea of making the unfamiliar familiar is very much how I feel about living in New York,” she said. “It’s a struggle to feel comfortable here. I just don’t feel normal.”

Johnson’s Fence with Grass similarly captures this sentiment, going beyond mere representation of the experience of displacement to challenge her own history and sense of the familiar. In this work she opposes Gaston Bachelard’s notion that “outside and inside form a dialectic of division.” Through the weaving together of a wooden fence from her childhood street and a wrought iron fence of the sort that demarcates the barrier between public street and private residence in New York City, Johnson hints at a continuum stretching between these divided states. The private history of her childhood fence is brought into a larger context where its previous significance becomes merely one layer within many layers of history. And with the motorized grass-bot continually banging into the wooden fence, Johnson captures the impossibility of escaping from the past. While the fence brought from Waco is left raw, the stoop fence is painted to replicate the texture of homes and fences in New York, where a continuous cycle of families moves into and out of the same spaces, painting the same walls and wrought iron gates over and over. The personal, or interior, memories of these locales—the dent in the wall from the lamp that fell or the vestige of green paint visible beneath the layers of red—are the result of specific actions that become indistinguishable from the collective, or exterior, experiences of these objects and places. Linking one bare fence and one heavily painted, Johnson suggests the fluidity between inside and outside, private and public, familiar and unfamiliar, while reinforcing a sense of permanence present in one’s past.

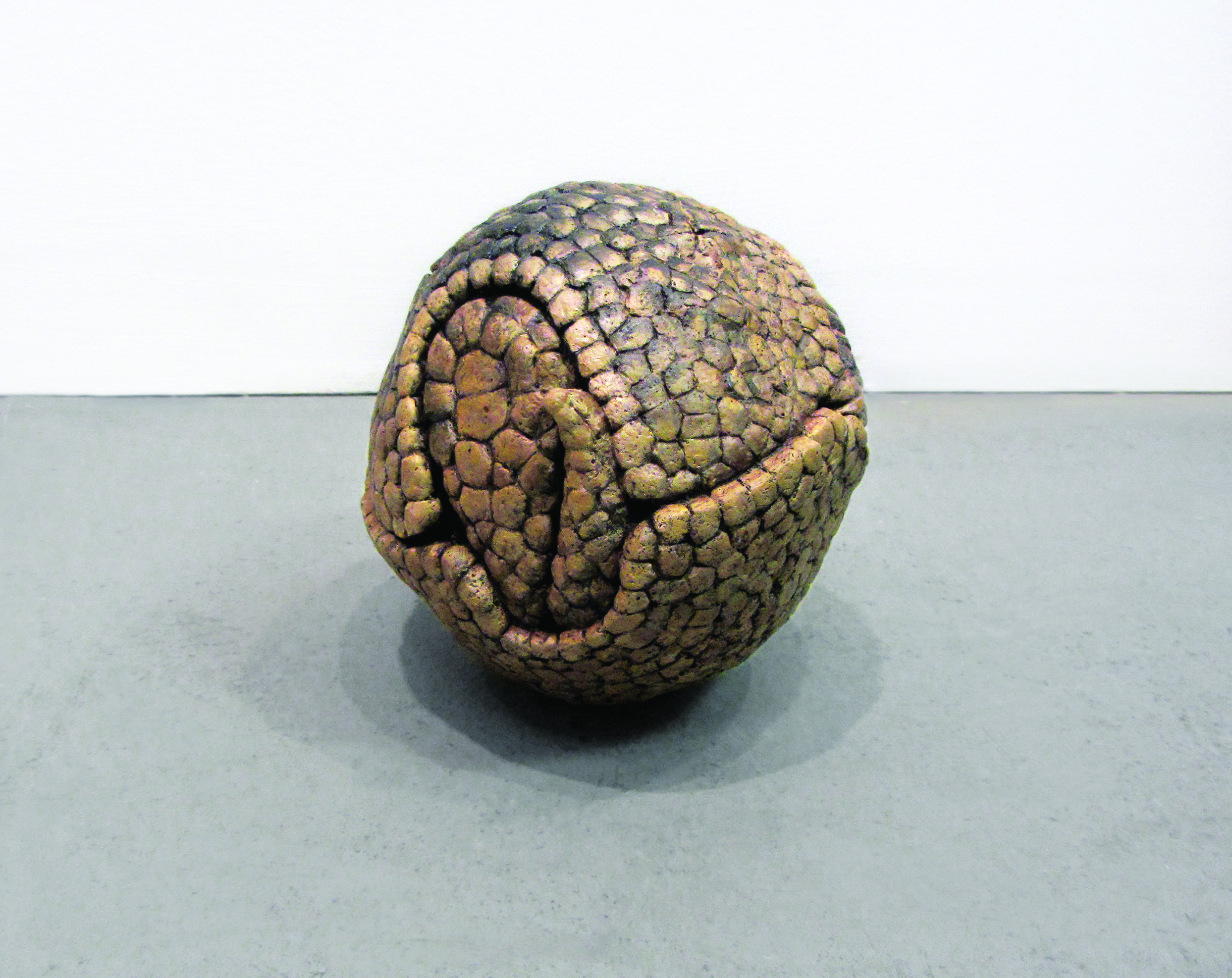

Tucked off to the side of the fence is a cast hydrocal gypsum and fiberglass armadillo. Johnson says Texans see armadillos the way New Yorkers see rats: both animals are disgusting and ubiquitous. It may be a surprise, then, that the presence of the armadillo solidifies the exhibition as a form of self-portraiture. Johnson calls the creature—which can recoil within its scaly shell for protection when scared—her spirit animal. With its exterior armature, the armadillo counters the other, physically and symbolically vulnerable works on view, offering a metaphorical manifestation of Johnson’s examination of interior and exterior. The hoses are constructed of aluminum, which is covered in rope and silicon and then painted, leaving them dependent upon an internal structure for support. The armadillo, on the other hand, has an external structure that offers protection and safety in spaces that are unfamiliar and threatening.

As French Romantic writer, historian, and diplomat François-René de Chateaubriand wrote, “Every man carries within himself a world made up of all that he has seen and loved, and it is to this world that he returns, incessantly.” Johnson’s exhibition is evidence of the timelessness of these words and a reminder to us that alienation, and a yearning for home are in fact universal.

(Young Art Critic Writer) Sara Roffino is a writer, editor, and graduate student based in New York City. Following undergraduate studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, she taught literacy skills in a NYC public high school while earning a master's degree in education. Sara was a Fulbright scholar in Portugal in 2009–10. Since returning from Europe, she has worked at the Brooklyn Rail, as the managing editor, and at Art+Auction magazine, where she is currently a senior editor. Sara is also studying for a master's degree in art history at Hunter College, and working as a research assistant for the art historian Barbara Rose.

(Young Art Critic Mentor) Nancy Princenthal is a New York-based critic and former Senior Editor of Art in America; other publications to which she has contributed include Artforum, Parkett, the Village Voice, and The New York Times. Her book Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art (Thames and Hudson) was published in June 2015. She is also the author of Hannah Wilke (Prestel, 2010), and her essays have appeared in monographs on Shirin Neshat, Doris Salcedo, Robert Mangold and Alfredo Jaar, among many others. She is a co-author of two recent books on leading women artists, including The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium (Prestel, fall 2013). Having taught at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College; Princeton University; Yale University, Rhode Island School of Design, Montclair State University and elsewhere, she is currently on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts.

This essay was written as part of the Young Art Critics Mentoring Program, a partnership between AICA-USA (US section of International Association of Art Critics) and CUE, which appoints established art critics to serve as mentors for emerging writers. In 2014, CUE joined forces with Art21, combining the Young Art Critic program with the Art21 Magazine Writer-in-Residence initiative. Each writer composes a long-form critical essay on one of CUE’s exhibiting artists for publication in CUE’s exhibition catalogue, which is also published by Art21 in its online magazine. Please visit aicausa.org for more information on AICA-USA, or cueartfoundation.org to learn how to participate in this program. Any quotes are from interviews with the author unless otherwise specified. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior consent from the author. Lilly Wei is AICA’s Coordinator for the program this season. For additional arts-related writing, please visit on-verge.org.

This essay was written in conjunction with Tamara Johnson: NO YOUR BOUNDARIES, on view at CUE February 13 – March 23, 2016.