Writer: Constanza Salazar

Essay Mentor: Carson Chan

This essay was produced in conjunction with the exhibition Insight Outsight by Ling-lin Ku, with mentorship from Agnieszka Kurant and on view at CUE Art Foundation from November 9 – December 22, 2023. The text was commissioned as part of CUE’s Art Critic Mentorship Program, and is included in the free exhibition catalogue available at CUE and online.

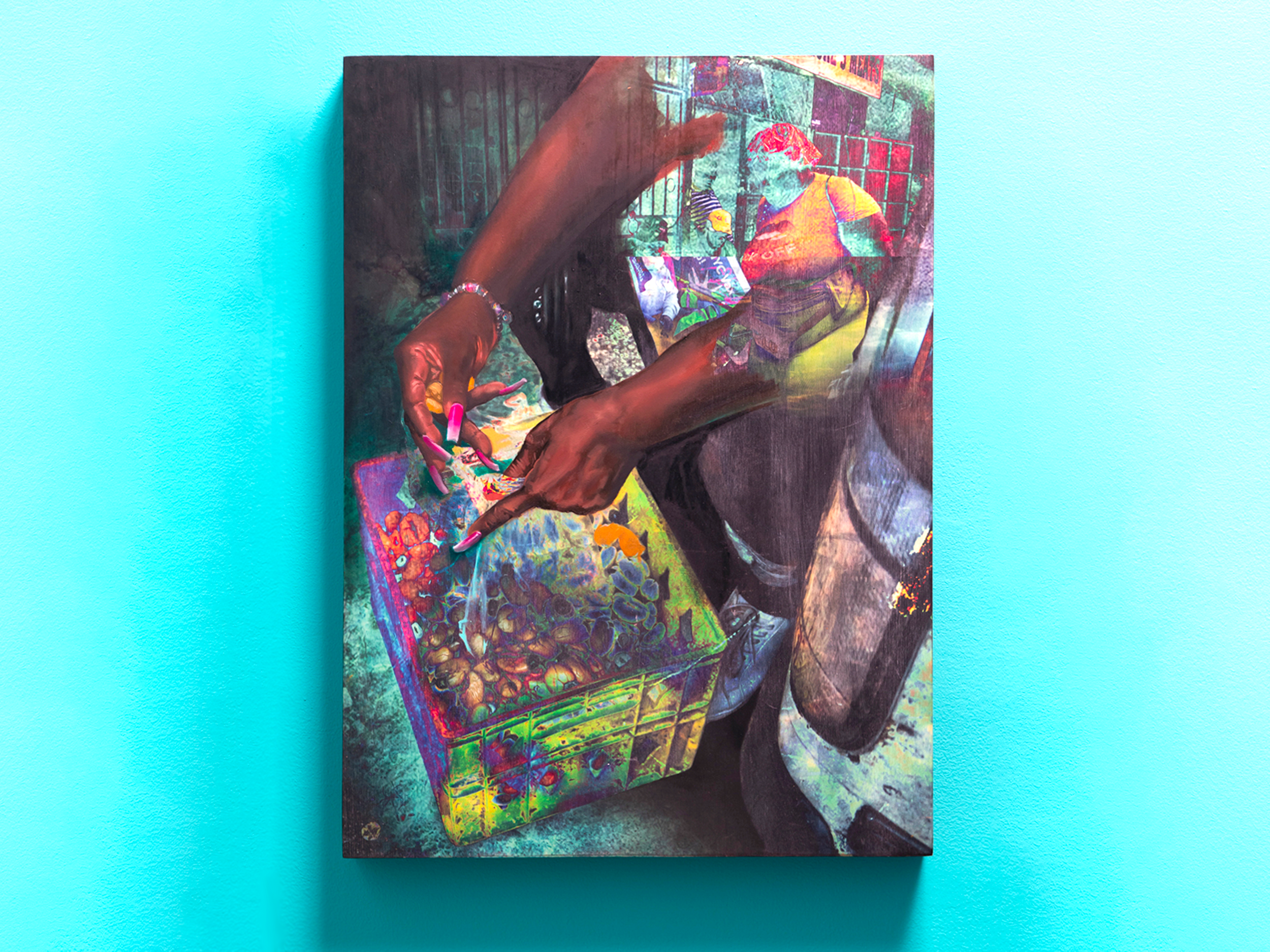

Installation view of Insight Outsight by Ling-lin Ku, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

The origin of the term “bug” in computer culture is often attributed to U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, after an incident involving a moth inside Harvard University’s Mark II computer. This story exists alongside others, like that of Thomas Edison using the term to first signify a defect in his phonograph, but it nevertheless raises the question of how insects, or bugs, have become commonplace in popular computer slang, a linguistic relationship we often take for granted. In Insight Outsight, multimedia artist Ling-lin Ku exhibits playful sculptures that reveal the viewer’s linguistic and ecological entanglement with insect life, reminding us that digital media has always had very real material properties and effects, and compelling us to imagine a world beyond ourselves.

I first became aware of the metaphorical and material intersections between nature and technology after reading Jussi Parikka’s Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology, published in 2010. In the text, Parikka uncovers how insect life has been translated to modern media technologies since the 19th century. For instance, humans speak about a hive to signify distributed intelligence, a swarm to describe coordinated organization, and the web to delineate connected systems and networks. In all these metaphors, insect life is used to orient us to the possibilities of communication, coordination, and even architecture, or at least to implement tactics of modern power structures. Parikka, however, recovers the inhumanity of media to say that “there is a whole cosmology of media technologies that spans much more of time than the human historical approach suggests. In this sense, insects and animals provide an interesting case of how to widen the possibilities to think about media and technological culture.”¹ In Insight Outsight, Ku builds upon this dialogue, opening up a new dimension to think through the parallels between insect and human technological life.

Installation view of Insight Outsight by Ling-lin Ku, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

Ku’s works emerge as fantastical experiences that one slowly uncovers. With the use of computer technologies, contemporary art today often presents spectacles that thrive on the immediacy and overconsumption of images, eliciting a feeling of immersion, such as in works by Refik Anadol, Cao Fei, and teamLab. By contrast, in Ku’s multi-media sculptures, she emphasizes a subtle form of discovery that provokes feelings of delight and surprise on a micro scale. The title of this exhibition, Insight Outsight, suggests tensions between multiple layers of seeing and being seen, including sight facilitated by technological tools such as a computer screen or camera. Take the 3D printed sculpture with a 404 error code engraved onto the body of an insect, in which the code is at first glance barely visible due to its transparency. Its conceit lies in its multi-layered significance. In computer language, the 404 error code tells a computer user about a missing requested webpage. In Ku’s sculpture, the viewer witnesses the insect transforming into a digital “bug” frozen in time. Caught in the process of metamorphosis between insect and digital media, the sculpture’s form is rendered as a “glitch.” While glitches are typically faults or errors that prevent the functioning of various types of operations, in Ku’s works, they also represent opportunities for interspecies understanding and relation.

Installation view of Insight Outsight by Ling-lin Ku, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

The tactics of camouflage and mimicry utilized by Ku throughout the exhibition aid in the viewer’s visceral engagement of the sculptural works in the show. Despite its military genealogy, camouflage has recently been taken up as an urgent artistic counter-strategy, often through performance. Artists such as Hito Steyerl, Leo Selvaggio, and Adam Harvey, among others, have used camouflage to protect themselves against surveillance technologies, in particular facial recognition. Ku’s works similarly employ a sense of concealment as a visual strategy against the proliferation of images that mark our contemporary condition. For instance, she installs non-functioning surveillance cameras throughout her work as a strategy to instill a feeling of being watched. This uncanniness through artifice elicits in viewers contrasting reactions of both curiosity and self-regulation. However, rather than returning to the postmodern screen-based landscape where once intrusive surveillance technologies have become commonplace, Ku orients the viewer toward the differences and similarities by which insects and humans view the world, either through their own eyes or assisted with technologies like cameras. Insect vision, which creates a mosaic of images through compound eyes, and technological vision, which pixelates images in the works, come together to signal the way humans have adopted non-human vision into our day-to-day lives.

In another of Ku’s sculptures presented as part of the exhibition, fluorescent green caterpillars crawl inside the crevices of the numbers on a bright yellow flood scale. While scales such as this one are typically used to measure the severity of floods, in Ku’s work, it and the caterpillars take on multiple meanings. Witnessing their slow ascent of the scale, it is difficult not to anthropomorphize them, giving them human qualities of sentience and wondering about their insect logic. What do insects know that we do not? What can they tell us about the world? As they climb the structure (metaphorically related to humans climbing social ladders), their instinct for survival undeniably has an overtone of ecological urgency, of surviving the rising tides brought by climate change. In this work, viewers are reminded that they belong to a larger macrocosm of diverse species life, and the anthropocentrism of humans is momentarily overturned to highlight this ecological reality.

Installation view of Insight Outsight by Ling-lin Ku, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

Technology and nature further intertwine in Ku’s artistic practice. Through the digital fabrication of organic forms in 3D animation, surveillance cameras, and 3D printed glitched objects, Ku emphasizes the materiality and objecthood of nature rather than merely relying upon technology in itself. Ku offers us moments of respite from our technological daze to return to the world and its real material properties and effects. There is a kind of ecological recalibration in the works that provoke viewers to simultaneously reflect upon their finitude and the world they will leave behind. For instance, a plastic straw that doubles as a centipede is not simply a symbolic placeholder for the ecological effects of human waste, but also as a real posthuman entity that, nevertheless, survives in the Anthropocene. It is said that plastic takes up to 1,000 years to decompose, but what happens in the meantime? Insects, like all animals that came before human civilization, have gone through eons of adaptation and survival. Humans are usually not privy to waste and its lifespan, and yet waste, like many forms of insect life, will outlive us.

In Insight Outsight, viewers first encounter what appears to be a playground of insects engaged in a game of hide-and-seek, slowly emerging and withdrawing from sight. Over time, one develops a newfound understanding of humanity in this macrocosm between nature and technology. In the end, we are left with a sense of transitory belonging and a perspective that will linger for some time.

Endnotes

[1] Jussi Parikka, Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), xiv.

About the Writer

Constanza Salazar is a Canadian art historian, educator, and writer based in New York City. Her work centers the histories and theories of technology, new media, and art. Salazar has presented papers internationally, and her writing has been published in Momus, Afterimage, and Internet Histories, among others. She is currently working on a book project based on her Ph.D. dissertation, entitled Embodied Digital Dissent: Co-opting and Transforming Technologies in Art, 1990-Present. She received a Bachelor in Fine Arts and Philosophy at the University of Waterloo in Canada, a Master in Art History at the University of Guelph in Canada, and a Ph.D. from Cornell University in New York.

About the Writing Mentor

Carson Chan is the inaugural Director of the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment at the Museum of Modern Art, and a Curator in the museum’s Department of Architecture and Design. He develops, leads, and implements the Ambasz Institute’s research initiatives through a range of programs, including exhibitions, public lectures, conferences, seminars, and publications. Before joining MoMA, he worked as an architecture writer, curator, and educator. In 2006, he co-founded PROGRAM, a project space and residency program in Berlin that tested the disciplinary boundaries of architecture through exhibition making. Chan co-curated the 4th Marrakech Biennale in 2012, and the year after he served as Executive Curator of the Biennial of the Americas in Denver. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Cornell University and a Master of Design Studies from Harvard Graduate School of Design. His doctoral research at Princeton University tracks the architecture of public aquariums in the postwar United States against the rise of environmentalism as a social and intellectual movement. He is a founding editor of Current: Collective for Architecture History and Environment, an online publishing and research platform that foregrounds the environment in the study of architecture history.

About the Art Critic Mentorship Program

This text was written as part of the Art Critic Mentorship Program, a partnership between CUE and the AICA-USA (the US section of International Association of Art Critics). The program pairs emerging writers with art critic mentors to produce original essays about the work of artists exhibiting at CUE. Learn more about the program here. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior written consent from the author.