Writer: Sarah Aziza

Essay Mentor: Dina Ramadan

This essay was produced in conjunction with the exhibition A thought is a memory, curated by Noel Maghathe, with mentorship from Sara Raza and on view at CUE Art Foundation from March 23 – May 13, 2023. The text was commissioned as part of CUE’s Art Critic Mentorship Program, and is included in the free exhibition catalogue available at CUE and online here.

The first time I remember hearing the word “Palestine,” I was about six years old. The moment is captured on a family video that shows my father seated in the corner of our playroom, leaning a globe on his knee. “Daddy is from a place called Palestine,” he says, holding up the round replica of the world. In my mind’s eye, I recall vividly the thin lines of the painted topography, my father’s fingertip abutting the words ISRAEL/PALESTINE. [1] Still only barely able to read, I stared at the ink, willing it to enter me, to reveal its mystery.

Most second- and third-generation immigrants retain a version of this threshold in their childhood memories. The idea of homeland arrives, haloing all things with elsewhere and before. The self-evident, singular present gives way to a messy enmeshment with history. The child discovers that she is part of a multitude she has not seen, her body a nexus of others’ memories. Whether her family’s immigration was due to force or choice, her life becomes a counterpoint, cast in relief against what might have been.

Soon, she will also have to contend with the imagination of those outside her ethnicized group. الفكرة ذكرى / A thought is a memory, a group exhibition at CUE Art Foundation curated by Noel Maghathe, presents work by four artists—Zeinab Saab, Kiki Salem, Nailah Taman, Zeina Zeitoun—who all identify as Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA). [2] Each has confronted the limited, neo-Orientalist expectations which too often frame the work of SWANA artists through the pseudo-curiosity of an audience that seeks not to learn, but to reaffirm the limited and familiar. For such consumers, desirable cultural production satisfies a lurid, post-9/11 tendency to both otherize and “humanize” the (particularly Muslim) “Middle Eastern” subject. Among the most celebrated works are those presenting spectacles of suffering, glossed folklore, or flamboyant rejections of supposedly-traditional barbarity.

These stifling expectations from non-SWANA audiences are often compounded by an internal pressure to create art that conveys unadulterated affection and nostalgia for specific versions of a supposedly-collective past. We are expected to account for, and in fact constitute, notions of self and nation based not in personal experience but in contrived vocabularies—based either on the presumptions of outsiders or a duty to our elders’ (often sentimental) memories. In each, complexity is elided, as we are called upon to represent communities that may be much more expansive or diverse than what we know.

A thought is memory contemplates these gaps through imaginative gestures that create a space beyond overdetermined terrains. The show presents works that are diverse in medium and material, from painting to digital animation, film, photo collage, installation, and soft sculpture. The result is a chorus of new languages, one that revels in declarations of futurity springing from living, multi-varied histories.

Installation view of A thought is a memory, curated by Noel Maghathe. Presented by CUE Art Foundation, 2023. Photo by Filip Wolak.

Many of the works in the show are exercises in triangulation, as the artists move imaginatively around—and through—collective silences. Zeina Zeitoun contemplates the ways in which absence and loss haunt her relationship with both her father and the Lebanon he left behind. In the film work Happiness is the Sea and my Baba Smiling, Zeitoun splices together fragments of a family video that depict the artist as a little girl splashing and clinging to her father’s neck as they swim in the Mediterranean. The footage is cut with a black screen and white text subtitling the artist’s one-sided conversation with her father. “There is a scar on the back of your leg… I asked you where you got it from…” The closing segment, which shows Zeitoun and her father in split-screen facing away from one another, confirms the film’s ultimate experience of a love defined by innumerable unknowns, omissions both chosen and inevitable.

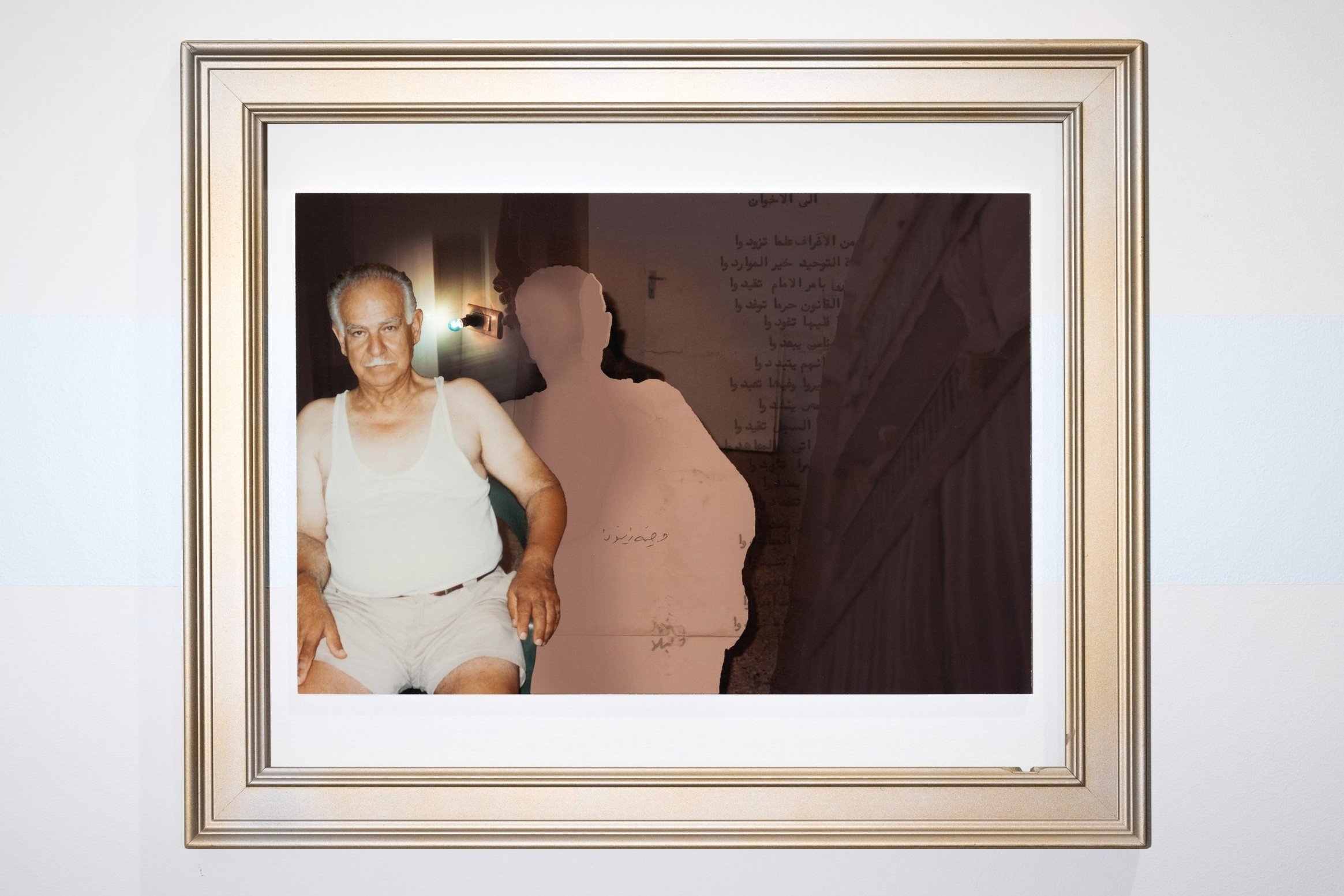

In Zeitoun’s collages, composed of photographs and film stills, old flight tickets, and snippets of text, the artist’s family archival material provide means to contemplate ancestral mystery. In one work, bright depictions of waves and hills are disrupted by human figures that are mostly truncated and obscured. In another, the figure of Zeitoun’s grandfather appears dislodged, sliding out of frame against what looks like scraps from a diary. Paper-thin, these layers evoke dimensions that are not there, objects beyond grasp. A particular kind of memory: a grief for that which might have been.

Zeina Zeitoun, Wajih Zeitoun, 2023. Photo by Filip Wolak.

Nailah Taman also embeds familial artifacts in their work, creating makeshift meeting spaces between the past and the artist’s imagination. These spaces flicker with the light of alternate lives and intimacies, forming original collaborations with the past. In this experimentation, Taman joins Zeitoun in a practice I term speculative memory. While Zeitoun’s speculation slants toward mourning, Taman is eager to reach for that which is only made possible with distance and time.

In Taeta’s Tabletent, Taman creates a portal-shelter where then, now, and future meet. They began with a partially-embroidered tablecloth left incomplete by their Egyptian grandmother (taeta). After stumbling across the discarded item, they partnered with their taeta’s living spirit, constructing a moveable dwelling place embellished with objects from their personal and familial past—seashells, an inhaler, their fiance’s empty bottle of testosterone.

Through this work, Taman collapses barriers of time and space, creating juxtapositions that were once impossible. Bonds of birth and blood are made contemporaneous with Taman’s adulthood, their chosen loves. Their queerness is placed into proximity with their grandmother’s lips. Threads stitched in the 1980s of the AIDS crisis live alongside objects that Taman rescued from COVID-era trash piles on the street. Hoisted as a shelter that evokes either childhood games or iconic Bedouin camps, it has the effect of welcome, wonder, even nurturing. Perhaps the present has something to offer the past, and not only the other way around.

Nailah Taman, Taeta’s Tabletent (detail), 2021. Photo by Filip Wolak.

Zainab Saab’s work, which includes a series of experimental paintings on paper, emerges from their own path toward self-determination and futurity. The gestures are hard won—growing up in the uniquely-large Arab American community in Dearborn, Saab faced intra-community pressure to conform to a particular form of Lebanese femininity. As such, familial and communal interpretations of Arabness—as well as gender and religion—felt overdetermined, and like something to escape.

Saab’s paintings signal a successful jailbreak. In contrast to the classic diasporic project of capturing an evanescent, collective past, Saab seeks to recover their inner child. The series Visual Decadence, for example, emerged from pandemic experimentations, when Saab bought themself the colorful gel pens they once yearned for as a child. The works are boisterous, ringing with vivid colors that vibrate and shimmer in abstraction. Both geometric and fluid, and accompanied in the show by similar large-scale works with titles such as You Wanted Femininity, But All I Have is Fire and Can’t A Girl Just Spiral In Peace?, Saab’s paintings are windows into youthful mischief, flamboyance, and joy. Together, they are an exuberant declaration of presence, a claiming of space in the here and now.

Zeinab Saab, Visual Decadence, 2022. Photo by Filip Wolak.

Kiki Salem also conceives of a vividly-imagined future, incorporating materials both inherited and bespoke. Salem’s works call back to their Palestinian heritage through Islamic architecture as well as traditional embroidery. Drawing upon the shapes and patterns of each, the artist brings these historically-rich legacies into endless, digital life. In A thought is memory, Salem presents projections and paintings that occupy both sides of large, handmade screens hung from the gallery ceiling. FOLLOW THE LEAD(ER) riffs on a diamond-and-spade pattern from Islamic tiling, the animation alternating between oranges, greens, purples, and golds. In What is Destined For You Will Come to You Even if it is Between Two Mountains, Salem draws on the eight-pointed star of Jerusalem, creating an interlocking spread of shapes in which color pulses outward from a red center, evoking a throbbing heart. Salem invites these would-be static symbols to breathe—and to dance.

This hypnotic effect splices together the ancient and modern in a way that speaks to the relentless march of time. It also gestures to the particularly Palestinian search for ever new and ingenious ways to transcend the obstacles placed between us and our homeland. Bursting with unapologetic color, Salem’s animations move ceaselessly, telling us that Palestine will exist in the future. There are new memories to come.

Kiki Salem, What is Destined For You Will Come Even if it is Between Two Mountains, 2021 (L) and FOLLOW THE LEAD(ER), 2022 (R). Photo by Filip Wolak.

For all four artists, that which is culturally “Arab” is imbued into their work with a subversive subtlety, present in accents and glimpses such as embroidery, geometry, mosaic, and text. When these visual aspects appear, they do so on their own terms, original and un-beholden to precedent or cliché. The effect is thrilling; one cannot help but feel a sense of the future, an assurance that there is more—at last and as there has always been—to being SWANA than forever-longing for the past.

These nuanced, imaginative forays are more than pleasurable—they are necessary. For all the external demands placed on idealized narratives of Arab American experience, much of our diasporic memory is shrouded in personal pain. Like so many Arab American families living on the far side of two centuries of Western colonization, [3] war, and upheaval, my relatives were selective in their retelling of the past. As a child, I often sat and stared at photos of my father and grandmother. Grainy and grayscale, in a mid-1960s Gazan refugee camp, their faces were grave and beautiful. Around them lay evidence of chaos: the glare of sunlight hitting debris, stones strewn around my father’s bare feet.

Looking at these photos filled me with a mixture of longing and alarm. I could not comprehend the young boy as my father, the somber young mother as the same woman who now filled our kitchen with the fragrance of frying onions, maramiya, and sumac. There was an infinity between ISRAEL/PALESTINE and our home in northern Illinois, which my father’s brief geography lesson did little to fill. The first word in that backslashed name—Israel—was a topic too painful to broach, as was Nakba, its synonym. Aside from a few token stories, my parents leaned on the American “melting pot” mythos, choosing to believe its promise to obliterate the unique textures of our pain. And so, I joined many others who inherited a form of double-erasure. Together, we are left trailing in the wake of opaque histories, pondering scraps in the periphery of photographs, secrets tucked in silences.

A thought is a memory wades through these fragments, arching between the past and a diasporic story of the future. It converges times and places—the gone, the current, the never-were, the yet-might-be. The works brought together by Noel Maghathe—whose curatorial practice centers the hybridity, diversity, and community of artists of the Arab American diaspora—create something beyond their sum: a sense of multiplicity, of mystery that feels exciting rather than terminal. A viewer may feel something akin to what I feel staring at photos of two strangers who are also family, who are also me. A sense of yearning and bewilderment. Of utter knowledge that is only waiting for the right language. Perhaps, in the kaleidoscope of ephemeral movement, hypnotizing color, otherworldly glyphs, and muted ink, the viewer finds forms that resonate. Much like Etel Adnan’s symbolic language, these expressions could be ancient, extra-terrestrial, or both. Just like us.

Endnotes

[1] When searching for "Palestine" on Google Maps, the map zooms in on the Israel-Palestine region, and both the Gaza Strip and West Bank territories are labeled and separated by dotted lines. But there is no label for Palestine. Apple Maps, similar to Google, zooms in on the region but doesn't label anything as Palestine. [Fact check: Google does not have a Palestine label on its maps, USA Today May 22, 2022].

In moments of despondency – or, for others no doubt, mere realism – it can be tempting to answer the question “Where is Palestine?” with “Nowhere”: nowhere geographically, nowhere politically, nowhere theoretically, nowhere postcolonially. [Where is Palestine? Patrick Williams & Anna Ball (2014), Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 50:2, 127-133].

[2] SWANA is a term increasingly used to situate the region and its peoples in geographically neutral terms, as opposed to the Euro-centric political orientation embedded in “Middle East.”

[3] Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798; France’s colonization of Algeria began in 1830, of Tunisia in 1881, and of Morocco in 1912. Meanwhile, Britain colonized Egypt in 1882, and also took control of Sudan in 1899. Further colonial incursions followed.

About the Writer

Sarah Aziza is a Palestinian American writer and translator who splits her time between New York City and the Middle East. Her journalism, poetry, essays, and experimental nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, The Baffler, Harper’s Magazine, Lux Magazine, The Rumpus, NPR, The New York Times, the Asian American Writers Workshop, and The Nation among others. She is currently working on her first book, a hybrid work of memoir, lyricism, and oral history exploring the intertwined legacies of diaspora, colonialism, and the American dream.

About the Writing Mentor

Dina A Ramadan is Continuing Associate Professor of Human Rights and Middle Eastern Studies at Bard College and Faculty at the Center for Curatorial Studies, where she teaches on modern and contemporary cultural production from the Middle East, decolonial movements, and migration. She has contributed to Art Journal, Journal of Visual Culture, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, and Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art and is currently completing a book on Egyptian art criticism titled TheEducation of Taste: Art, Aesthetics, and Subject Formation in Colonial Egypt (Edinburgh University Press). Her writing on contemporary art has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, e-flux Criticism, ArtReview, and Art Papers.

About the Art Critic Mentorship Program

This text was written as part of the Art Critic Mentorship Program, a partnership between CUE and the AICA-USA (the US section of International Association of Art Critics). The program pairs emerging writers with art critic mentors to produce original essays about the work of artists exhibiting at CUE. Learn more about the program here. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior written consent from the author.