THAT IS THEN. THIS IS NOW.

Curated by Irving Sandler and Robert Storr

September 9 - October 30, 2010

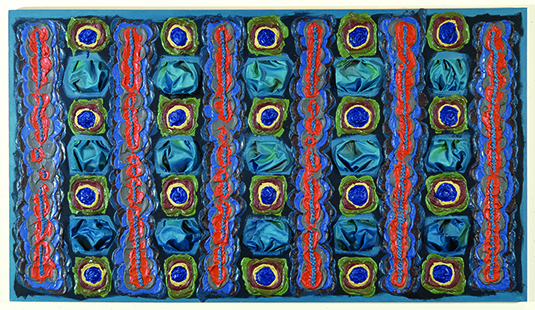

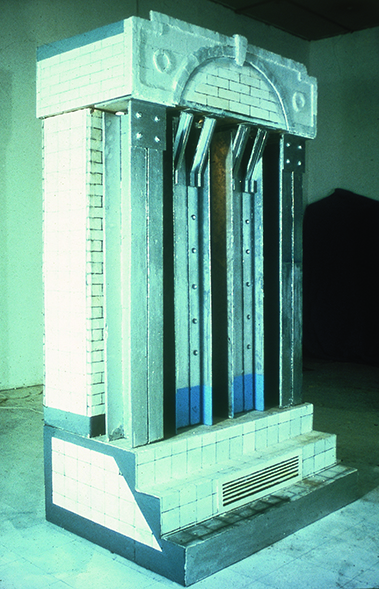

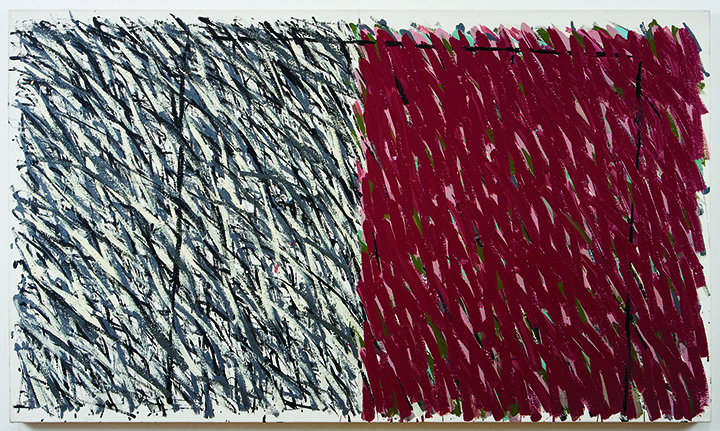

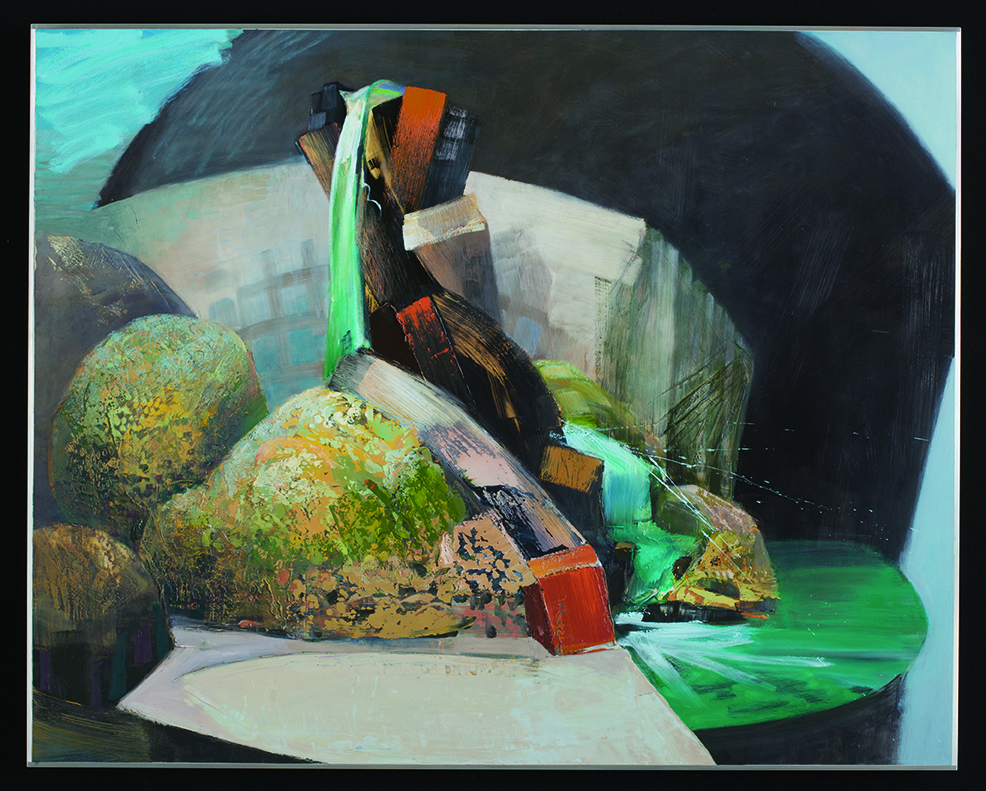

CYNTHIA CARLSON | DONNA DENNIS | DAVID DEUTSCHE | MARTHA DIAMOND

HERMINE FORD | MIKE GLIER | LOIS LANE | THOMAS LAWSON | KIM MACCONNEL

DIALOGUE: Irving Sandler & Robert Storr

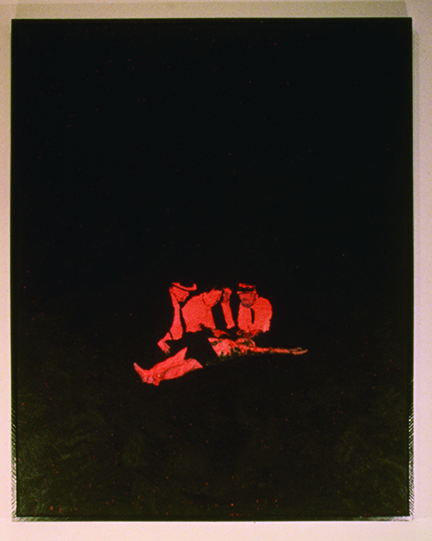

IRVING SANDLER: During the late 1960’s and 1970’s, the Vietnam War increasingly invaded the art world’s thinking. The war seemed interminable and was dispiriting. The body bags kept coming home, each one turning ever-larger numbers of Americans against the war. “Hey, Hey, LBJ, How many kids did you kill today?” The country seemed to be tearing itself apart. In 1968 alone, there were huge anti-war protests at the Pentagon, student uprisings in Europe and our own universities and massive demonstrations at the democratic convention in Chicago. This single year was a particularly depressing one, given the Tet Offensive, the My-Lai Massacre, the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the nomination of Hubert Humphrey for the presidency, and the election of Richard Nixon. And the news didn’t seem to get better.

ROBERT STORR: By 1975 the war was over and the year before that, Nixon has ignominiously left office as a result of the Watergate Scandal. Meanwhile, the economy lurched from bad to worse. The concerted action of the OPEC cartel caused oil prices to spike in 1973, setting the stage for the worst stock market crash since the Great Depression. In many ways the “Then” and “Now” referred to in the title of this show had similarities – war, debt, and a sense of fitful directionlessness. The 1970’s were international conflict, civil discord, polarization and stagflation; the present is international conflict, civil discord, polarization and a chain reaction of expanding and exploding economic bubbles. Swell times to make art.

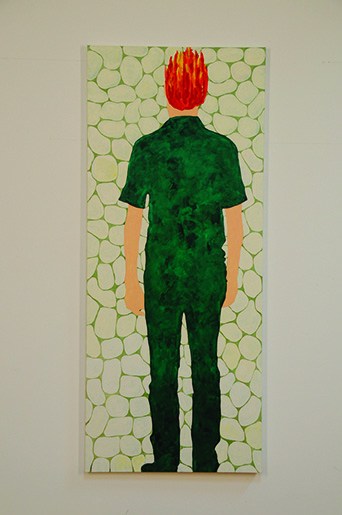

IS: You are right to highlight changes in the social situation in the 1970’s and the concomitant changes in the sensibility and the art of the decade. Two of the artists we selected did make political comments, Mike Glier, explicitly in his portraits of politicians, and Thomas Lawson ambiguously. As the Vietnam War wound down, Feminism emerged from the anti-war movement and generated the main political energies. Cynthia Carlson was a leading Feminist and her Pattern and Decoration painting exemplified its thinking. She established decoration and crafts, which historically had been the “work” of women but not considered “art,” into her high art and in the process to elevate the “work” of her sisters that preceded her.

RS. A number of older artists provided license for recourse to bluntness, awkwardness or indifference to “good tastes” and properly painterly table manners – those being the negative side of “painterly cuisine” as handed down from School of Paris art through preceding generations of The New York School. Chief among these was Philip Guston, who died in 1980 just as the transition from Pattern and Decoration and New Image art into Neo-Expressionism took place. His way with the brush – broad strokes, “crude” contours and a simplified palette – was a great encouragement to many younger artists whose work doesn’t outwardly resemble his but possesses the same fresh, “making up as I go along” quality. Another was Leon Golub, and along with him Nancy Spero. At the outset of the 1980’s, Golub and Spero began showing with artists half their age, as did Louise Bourgeois. Robert Colescott was another elder who refused to act his age. He refused to settle down and make pictures pleasing to mainstream taste-makers. Guston, Golub, Spero and Colescott were avowedly political artists while most of the people in this show were not. For the most part, the politically minded artists of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s shied away from painting and chose other, usually photo-mechanical means. But what of the others of our show, like Martha Diamond and Hermine Ford, both of whom could paint a “good” painting, but chose to pair away the Frenchness of inherited painting culture to get at something rawer.

IS: In 1969, I wrote that modernism implied a progression of new and original styles, emerging one after the other, each coming in to view, becoming established and then becoming dated. Make-it-new was the avant garde rallying cry; what had been done was not worth re-doing. I suggested the individuality of an artist’s vision and the artistry with which it is embodied in a work would be prized more than its innovation or up-to-datedness. Art had pressed to so many of its limits, that is, the edge where it could be taken for non-art. The avant garde ceased to exist because there had developed a large and growing public that no-longer responded in anger to unconventional art and while not eager for it, was at least curious or permissive. The audience for new painting and sculpture would have to prize the expressiveness and individuality with which artists use and mix known ideas and styles, how artists, in a phrase, re-make-it-new. This seems to me to be the situation for the artists we chose. They are among the earliest to have found themselves in the post-modern era.

RS: In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s art came to a fork in the road in that some artists, in effect, decided to make art “about” those second thoughts and others decided to explore the second thoughts, and see where they went. Irony was often part of the latter course. David Deutsch and Donna Dennis are both romantics of a sort – and both decided that invoking places that exist in the imagination was a kind of conjuring trick that could be performed without historicizing their ideas and explicitly footnoting their precedents in the American Scene. The results have a kind of dream fascination that irony subtly reinforces rather than undermines. They openly re-invite the suspension of disbelief whereas many of their contemporaries focus on disabusing the public of its illusions.

IS: Painting was still embattled, but in the Post-Modernist era, it not only seemed open to new possibilities, but able to claim art world attention, as it had not in the previous decade. As a painter, Thomas Lawson challenged so called Pictures Artists, most of whom made photo-based work and declared “Painting is Dead.”

The artists in the Pictures exhibition (Artists Space, 1977) seemed to make-it-new because they ransacked images from mass media. The show was arguably the timeliest of the late 1970’s. Most Pictures artists agreed with the curator of the show, Douglas Crimp, who vilified painting as pure lunacy. He not only put it down as reactionary, humanist and bourgeois, but he also claimed it had nothing new or relevant to say. Painting was, in a word, passe. Thankfully they did not go unchallenged. Thomas Lawson argued that if art was to be an agent of social change, as he believed it should be, painting was his medium of choice. Photo-based imagery – as well as so-called post-studio conceptual art – was culturally obscure and invisible to all but a few art theoreticians, and therefore useless as a means of social change. In contrast, painting still retained the authority to command public attention and hence could be politically effective. As for my response to these art-theoretical polemics, they amused me and, at the same time, I found them inconsequential, often fatuous, although they may have contributed to significant art.

CATALOGUE ESSAYS

The Not-so-Seventies Show by Peter Plagens

Painting/Writing/History by Martha Schwendener

Decorative Contemporary by Emily Warner