Sue Chenoweth

Curated by Susan Krane

February 3 - March 12, 2005

Sue Chenoweth was born in Plainview, Texas in 1953. It was in Texas that she began drawing with white rocks on sidewalks around the age of two. After moving to Phoenix, Arizona at the age of four, she began feverishly setting up drawing systems which included shorthand formulas for sketching. At age 14 she began to seriously study painting on her own by copying the works of Winslow Homer. From age fourteen to eighteen she worked under the direction of Marlyne Jones, an Arizona artist and teacher who trained Chenoweth to understand the value of drawing on a deep level. "I feel that I learned the important things during that time," she says, " I began using drawing as a way of ordering and relating." Sue went on to receive both her BFA and MFA from Arizona State University and is currently teaching Drawing and Painting at Metropolitan Art Institute, a College Prepatory High School in Phoenix. "I feel like I am on a mission," says Chenoweth, "In teaching, I want to perpetuate the legacy of drawing that was given to me as a youth. I want people to understand the importance of markmaking before that language is lost forever."

Susan Krane is director of the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona. She was director of the Art Museum, University of Colorado at Boulder (1996-2001); curator of modern and contemporary art at the High Museum, Atlanta (1987-1995); curator at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (1979-1987) and a fellow at the Walker Art Center (1978-79). Among her exhibitions and publications are Hollis Frampton: Recollections/Recreations (MIT Press, 1987); Albright-Knox Art Gallery: The Painting and Sculpture Collection: Acquisitions since 1972 (Hudson Hills Press, 1987); Lynda Benglis: Dual Natures (University of Washington Press, 1992); Max Weber: The Cubist Decade (University of Washington Press, 1992);Alison Saar: Fertile Ground (1992); Equal Rights and Justice (1994); Out of Order: Mapping Social Space (2000); Lesley Dill (2002); and Let's Walk West: Brad Kahlhamer (University of Washington Press, 2004). Krane received her BA from Carleton College, her MA from Columbia University and her MBA from the University of Colorado. She has served on the faculties of SUNY Buffalo, Emory University and the University of Colorado at Boulder, and is particularly interested in cross-disciplinary approaches to contemporary art.

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

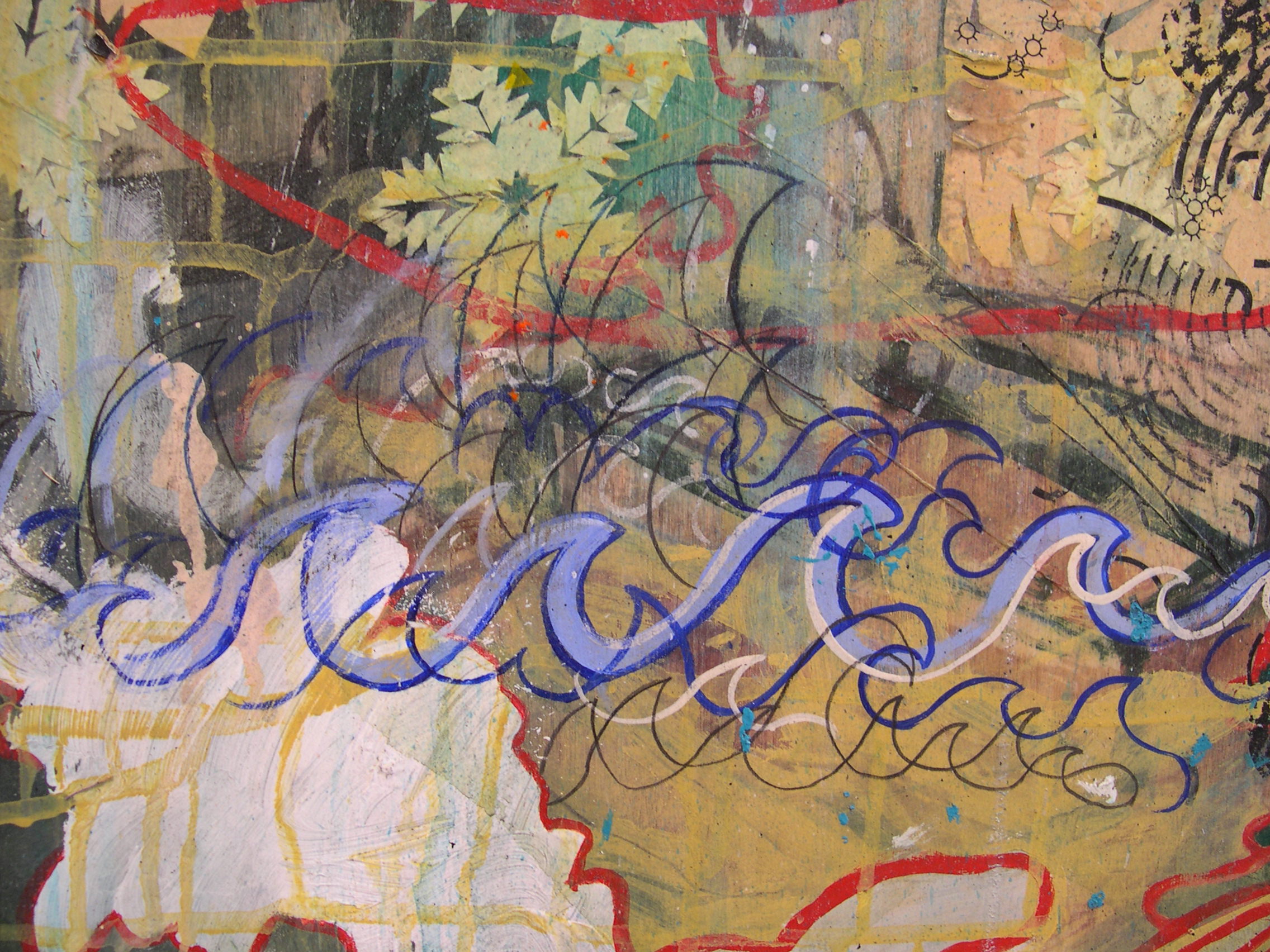

Painting becomes the terrain I travel. As the images ebb and flow, so do I. The marks are completely instinctive and unconscious and function as a type of reciprocal motion between the work and myself. These visible traces serve as a way of recording a primitive level of order. Even though each brushstroke and drawn line is completely subconscious, there is a profound sense of orderly direction to my art. Each mark is deliberately considered. The paintings are built on a scaffolding of Art History and all things formal. This is the stable base that allows me to try to employ a true artistic dichotomy. How does one think and not think at the same time? I want the viewer to experience the bits of feelings we all have behind our thoughts. I want them to remember things without language and explore their primal sensory essence. This essence is that which makes us human. Painting is about adaptation and change, transgression and redemption. It is the grand tale of 'Every Man' told through the language of drawing. I want to understand that language and be able to draw as easily as I breathe.

CURATOR'S STATEMENT

by Susan Krane

Sue Chenoweth makes art with urgency. Her scratchy, idiosyncratic drawings slip back and forth between abstract meanderings of the hand and representational musings of the mind. Images morph and dissolve at the edges, emerge from and submerge into the ground, as if spun from a surreal vortex. Her art sometimes seems to come from a place of sophisticated artistic awareness, confident enough to throw caution to the wind. At other times, it instead seems blatantly naïve, an affect of raw luck. Chenoweth balances on this knife's edge: she trusts and tends the self-propelled life of her art.

"I had to draw in order to survive," she explains. Artmaking, for Chenoweth, is a place where the compulsions of the mind find purpose and focus. She deliberately strives to give up conscious control - no small feat for her. Each painting, however, remains a collection of minute, labored decisions. She will talk in depth about choosing to turn a line here, or to drop a puddle of paint there. "I travel with them when I paint or draw them. Nothing is random. It's exhausting: I am riding that edge of its death," she explains.

Chenoweth's obsessive pictorial scrutiny belies her training and natural facility. She has drawn since she was a toddler and was raised with art. One grandmother was a painter, the other a weaver. As a child, she was given all the art books and supplies she wanted, contrary to other zones of family frugality. She had to turn down admission to California Institute of Arts due to illness and later attended Arizona State University. Her work rarely found favor with the faculty, most of whom considered it akin to outsider art - messy and uncritical. Although she admires the power of visionary art (most recently that of Henry Darger), Chenoweth is anything but unschooled. She has long taught high school art and art history and is a regular participant in the growing Phoenix-area art scene. She has, however, a hard-won gift of self-awareness, which validates an off-beat style that fits her like a glove.

During her recent stay in New York, Chenoweth was fascinated by the sheer excess of the city and high-end consumption, particularly high fashion. She was enthralled by designer shop windows and by her surprisingly intense desire for such finery - for "clothes like cotton candy that would melt in your mouth." Chenoweth was also perusing a collection of old prints she had bought at a library sale, The New Testament: A Pictorial Archive from Nineteenth-Century Sources (1) and later discovered the work of Piranesi, which she arranged to view in the print room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She became fascinated with the printmakers' confident and incisive line - a biting kind of drawing in her eyes.

These visual inputs fused in her mind and she launched the series "the Rich Man," in which she freely adapts 19th-century biblical illustrations of the Book of Luke. Chenoweth juxtaposes her appropriated religious iconography with frothy, doodling apparitions of fancy dresses. Desire twitches nervously in these works. Rather than make moralizing rants, Chenoweth wanted to depict the acuteness of such material enticements without resorting to picturing the object per se. Here, the state of wanting is an entrapment, but one that takes on a natural organic status. Dresses become glittering jewels, exotic bug-like chrysalises and vaporous spots of seductive color.

Chenoweth, operating far from the center of current critical discourse, takes risks of another, personal sort. "I go where my fear is," she says, "The fear now is drawing representationally. I want to capture the essence of a thing. How do you draw the sound of a bird singing before the sun comes up, when you are half awake?" And so Chenoweth's style is now willfully experimental - intense yet funky. Her art is disarmingly honest and welcomingly without pretense.

(1) Don Rice, ed. The New Testament: A Pictorial Archive from Nineteenth-Century Sources (New York: Dover Publications, I

View CATALOGUE