Richard Allen Morris

Curated by Siri Hustvedt

April 22nd – May 29th, 2004

Richard Allen Morris was born in Long Beach, CA in 1933. Morris, who received no formal art education, began exhibiting at the age of 26 and has had solo and group exhibitions throughout California since. This is his first solo exhibition in New York. Morris currently lives and works in San Diego, CA.

Siri Hustvedt was born in Northfield, Minnesota in 1955. In 1986, she received a PhD in English from Columbia University. She is the author of a book of poems, Reading to You, three novels, The Blindfold,The Enchantment of Lily Dahl, and most recently, What I Loved. She has also written frequently about art, most often for Modern Painters, but also for Art on Paper and other publications. Some of those pieces were included in a book of essays, Yonder, that was published in 1998. Princeton University Architectural Press will publish a book of her essays on painting, Mysteries of the Rectangle, in 2005.

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

I have never been able to put the right words together to describe my work. All I can say is that its foundation is rooted in abstract expressionism, anything else is just jargon.

CURATOR'S STATEMENT

by Siri Hustvedt

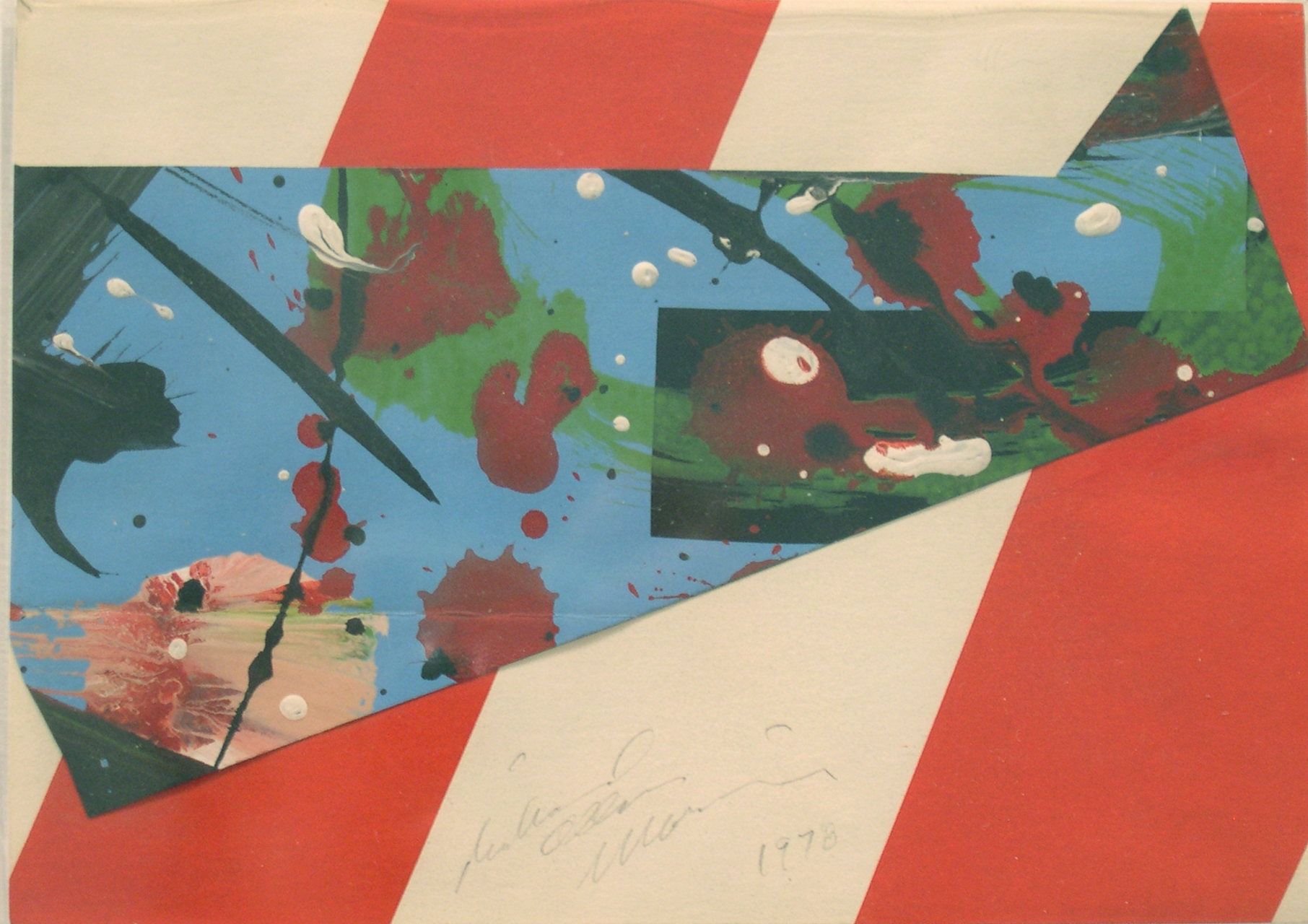

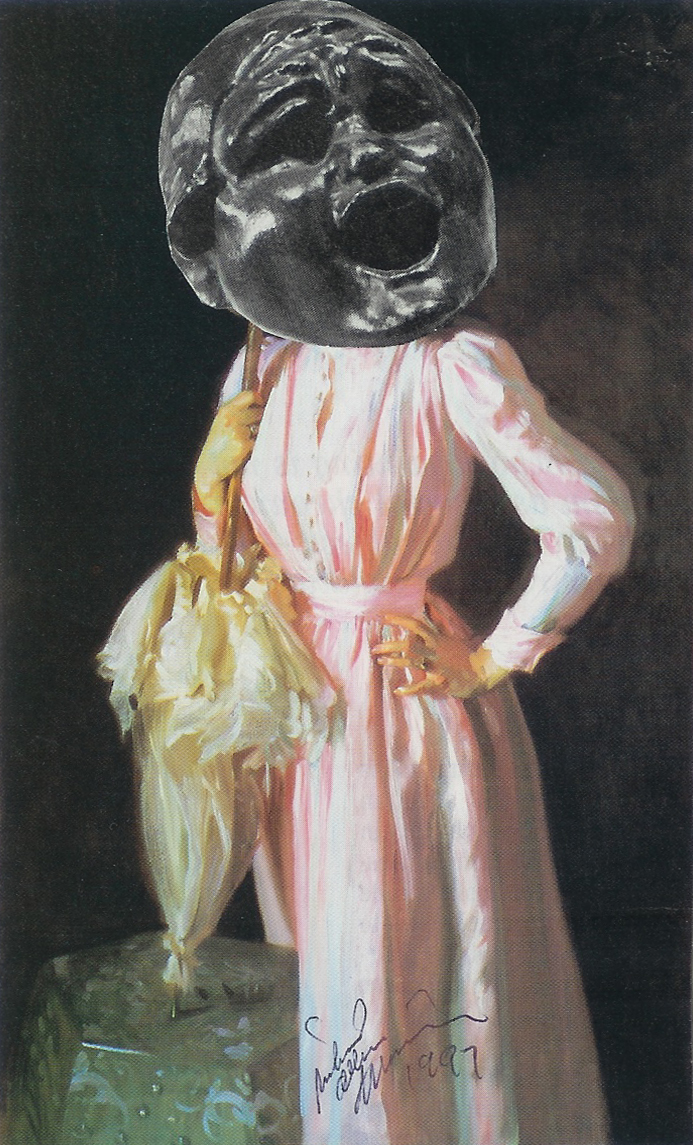

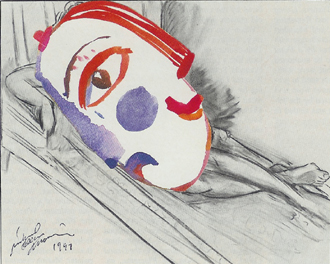

During the Korean War, Richard Allen Morris found himself on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific; a vessel the size of "a small town." It had its own craft shop where the men could find materials for projects of various kinds, including the then popular paint-by- number sets that promised to turn every ordinary Joe into a master painter. The tedium of matching color to digit, however, often proved too great, and weary sailors would abandon their half-finished boards to Morris, who altered and painted over them as he wished. During his time in Asia, he became fascinated with the art he saw around him and tried his hand at academically rendered Geishas and versions of the masks used in Noh plays. At the end of his service in 1956, he carried his remade number-paintings home with him in a cruise box.

I like this story about Richard Allen Morris because it is telling, not only of his beginnings as an artist, but of qualities he has retained throughout his career. After his stint in the navy and his participation in a war he refers to as "malarkey," he settled in San Diego and has never left. For almost fifty years, he has continued to work with materials he finds near him, putting scraps of cardboard, wood, cloth, and paper, including pages with text, as well as objects like yard sticks, model guns, and his own rejected canvases to artistic use. He explained to me that his works are mostly small because his studios have been mostly small. The size of his work is a product of necessity--a restraint he has turned into a virtue by making diminutive canvases, which, because they resist the preciousness of the delicate and tiny, feel strangely large. And his sensitivity to the many narratives of art history has never flagged. Over the years, he has filled one notebook after another with clippings and reproductions from magazines to create a dense personal catalogue of artists he admires, both living and dead. In his art and in his conversation, his references are myriad, ranging from immense figures like Giotto to the obscure Earl Kerkam, a painter I had to look up.

I discovered Morris's art through the painter, David Reed, who sent me a series of reproductions of pictures from the late fifties through the present that will be included in a show of Morris's work at the Krefeld Museum in Germany in October of this year. Immediately attracted, I visited David and looked at the fourteen canvases he owns, and my initial enthusiasm was confirmed. With any work of art, I inevitably ask myself: What am I seeing? Morris is a sublime colorist, and his pictures and constructions are often thick with paint, which makes them sensual, tactile things, but I am also seduced by other less tangible qualities: their intelligence, toughness, and humor. Over the years, Morris has looted from, adapted, reconfigured, revised, and anticipated artistic vocabularies to suit his own purposes. A single example of Morris's recurring reinvention and subversion may be seen in the guns to which he has returned throughout his career. He has produced both paintings of guns and gun objects. A canvas of a gun painted in 1965 gave me a start because it curiously prefigured the late, changed Philip Guston. Another gun six inches high and eight feet long, named with typical poetic verve "The Great Green Gat," is buried somewhere in Morris's studio. These guns, whether paintings or constructions are, of course, fictional. They don't shoot. Morris calls them a "cross between children's toy and African fetish." Because they necessarily unearth the mythic meanings of firearms in our culture but also look dramatically different from real weapons, Morris's guns tease the border between iconic representation and abstraction. Dressed up with brilliant color or sprouting unlikely limbs, the instrument of destruction is simultaneously undermined, enchanted, and reborn as art.

Richard Allen Morris is seventy years old. For nearly five decades, he has worked quietly and indefatigably in San Diego, beyond the purview of the larger art world, producing an impressive, sophisticated, and robust body of work. Although fellow artists like John Baldessari, James Hayward, David Reed, and Doug Melini have long championed his work, this important American artist is only now beginning to get the attention he has long deserved.

I offer my deepest thanks to David Reed

View CATALOGUE