The Oakes Twins

Curated by Lawrence Weschler

September 8 – October 29, 2011

Colorado-born visual artists and twin brothers, Ryan and Trevor Oakes, have been engaged in a conversation about the nuances of vision since they were children. They explored their mutual fascination with vision throughout grade school and during college at Cooper Union's School of Art in New York City. Since graduating in 2004, they've continued their dialogue through a body of jointly built art pieces that address human vision, light, perception, and the experience of space and depth in the particular way that they have come to understand it.

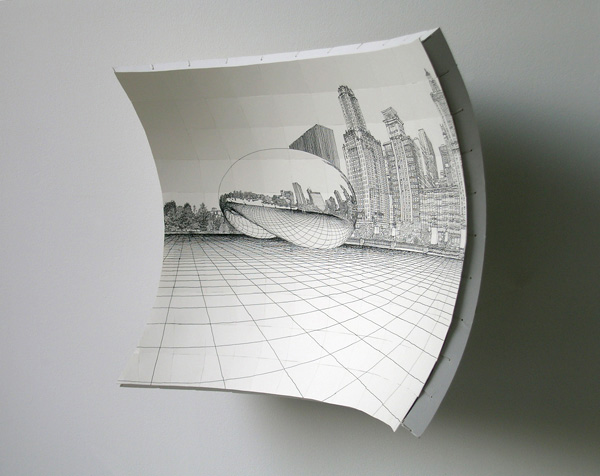

The Oakes' artwork is held in the permanent collections of The Field Museum and the Spertus Museum in Chicago. Their public art projects include a large-scale outdoor sculpture that debuted in Chicago's Millennium Park in the summer of 2009, and is now installed at O'Hare International Airport. They have exhibited and lectured about their artwork across the United States and abroad, most recently working with the Palazzo Strozzi Museum in Florence, Italy, during the summer of 2011.

In the fall of 2011, the brothers will do a drawing project at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. In the winter of 2012, they will be in residence creating an installation at The Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) in Troy, New York. In the fall of 2012, they've been invited back to Florence, Italy, to re-envision an artwork of Brunelleschi, creator of the first perspective experiment on the books, demonstrated around 1425.

Lawrence Weschler was for over twenty years a staff writer at The New Yorker, where his work shuttled between political tragedies and cultural comedies. His books of political reportage include The Passion of Poland (1984) and A Miracle, A Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers (1998). His "Passions and Wonders" series began with his biography of Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees (1982, recently reissued in an expanded edition, along with a counterpunctal volume on David Hockney, True to Life) and will culminate this month with the release of his latest collection Uncanny Valley (Counterpoint), which will include a long essay on the Oakes Twins. His Everything that Rises: A Book of Convergences won the 2007 National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. He is currently the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, and Artistic Director Emeritus of the Chicago Humanities Festival.

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

Art is the playground of the physical world.

Light is the medium of all visual art.

Any piece of visual material—art, nature, literature—that might spark awe in the mind will come through

the gates of the eyes.

—The Oakes Twins

Since birth we've been visually and tactilely focused. As kids we gravitated toward games that involved spatial play such as juggling and unicycling. As growing artists, we spent much of our time observing aspects of the physical world that we found commanding, such as noting that a bumble bee flies in a path of coiling figure 8's. We have always liked order and systems, and we're methodical.

Early on, for subject matter in our art, we tended toward the investigation of center points. Centrally oriented clusters where things collected, or from which they dispersed, seemed to be everywhere in the physical world—from atoms to the human embryo to city centers to planetary bodies. Their abundance gives them significance, and we chose to focus much of our early art around the investigation and creation of center points.

Within the territory of center points, light in particular became a primary focus. Light bursting into a growing sphere from its source; the eye extracting an inverted spherical burst of light from the air, converging at the pupil; and space as it appears to shrink to a vanishing point on the horizon line are among the center-point phenomena present within light. Light, the eyes looking via light, and the space they ultimately take in, thus became the core of our artistic exploration.

CURATOR'S STATEMENT

"The Whole Reason Perspective Happens"

Those being the words that one of the twins had scrawled beneath a quickly sketched diagram, on a little square yellow post-it note, words which in turn cracked up a fellow student friend of theirs at Cooper Union when he happened upon the note early on in the series of investigations that in turn would presently lead into the string of breakthroughs in the Twins's artistic practice—words that in turn bring a wide and winning smile to both the Twins's faces whenever they relate the story to this day. The Twins being identical, Ryan and Trevor Oakes, still in their late twenties, out of West Virginia though based in New York over most of the past decade; the breakthroughs being considerable (having caught the attention of the likes of David Hockney and Oliver Sacks and Jonathan Crary, who once, only slightly joshingly, described one of them—a method whereby the twins are able to, as it were, trace the visual world before them, as if with a camera obscura or camera lucida, though in fact without any equipment whatsoever beyond their own visual cortexes—as one of the most significant breakthroughs in the depiction of visual space since the Renaissance); and the investigations, actually, going back well beyond their time there at Cooper Union. For in much the way that some identical twins secrete uncanny private languages from early on in their lives—something these twins did not do—the Oakes boys have been engaged in a deep and probing conversation about the nature of perception that goes all the way back to their toddlerhood. Two individuals, that is, deeply seized by the core mysteries involved in what it is like to see with two eyes: engaged in a dialog about bifocality, stereoscopy, depth perception, peripheral vision, perspective, light foam (as they call it), chopstick focus (likewise), the splay of rays leaving light sources and the countersplay entering the eye's pupil, bodily awareness of visual cues, and on and on like that, ever more phenomenologically exacting and intellectually daring, for coming on three decades.

I met them a few years back at an evening devoted, as it happens, to the work of a different set of identical twins, Margaret and Christine Wertheim, whose investigations into hyperbolic space—and the crocheted coral reef project those investigations presently opened out onto (a whole other story, though one well worth pursuing on the web)—had momentarily rubbed up against some of the concerns of the Oakes boys. And as I say, I found the boys completely winning: the scale of their ambition almost jaw-dropping, but the lightness with which they carried it, the self-effacing openness of their curiosity, all of it quite fetching. I took to visiting their one room basement studio apartment about a block off Union Square—a veritable optical lab, a churning hive of experimentation (a pair of bunkbeds wedged discretely into one corner)—and to recording some of their stories in my notebook (for instance about the time, as kids, when they sat on tree stumps twenty feet apart and tried to work out what the depth perception of a creature with eyes that far apart might be like). Presently I wrote up an essay on their perceptual adventures and contributed it to the Virginia Quarterly Review (Spring 2009), but obviously that piece was only able to relate things up to that point, and the churning has continued apace.

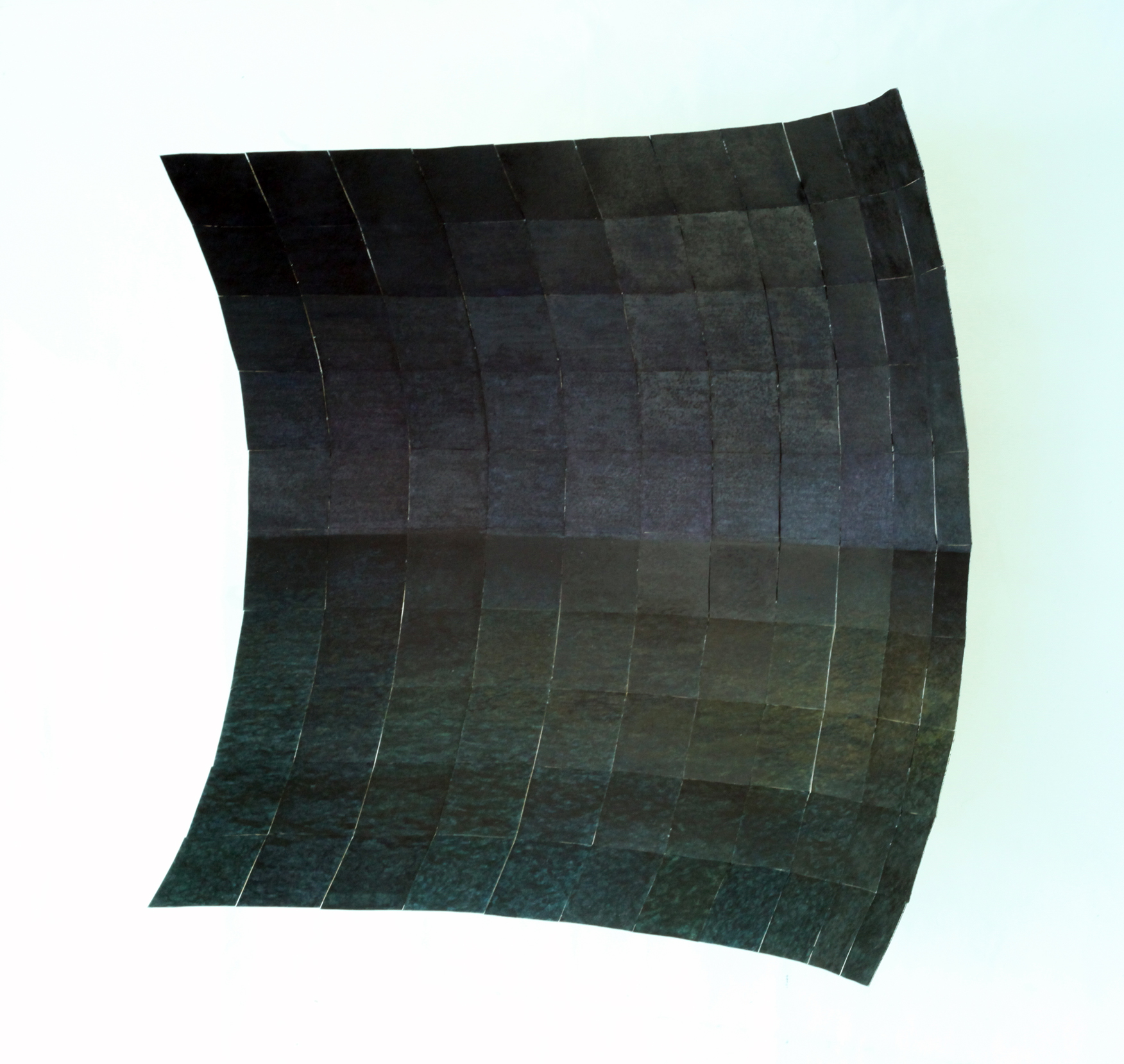

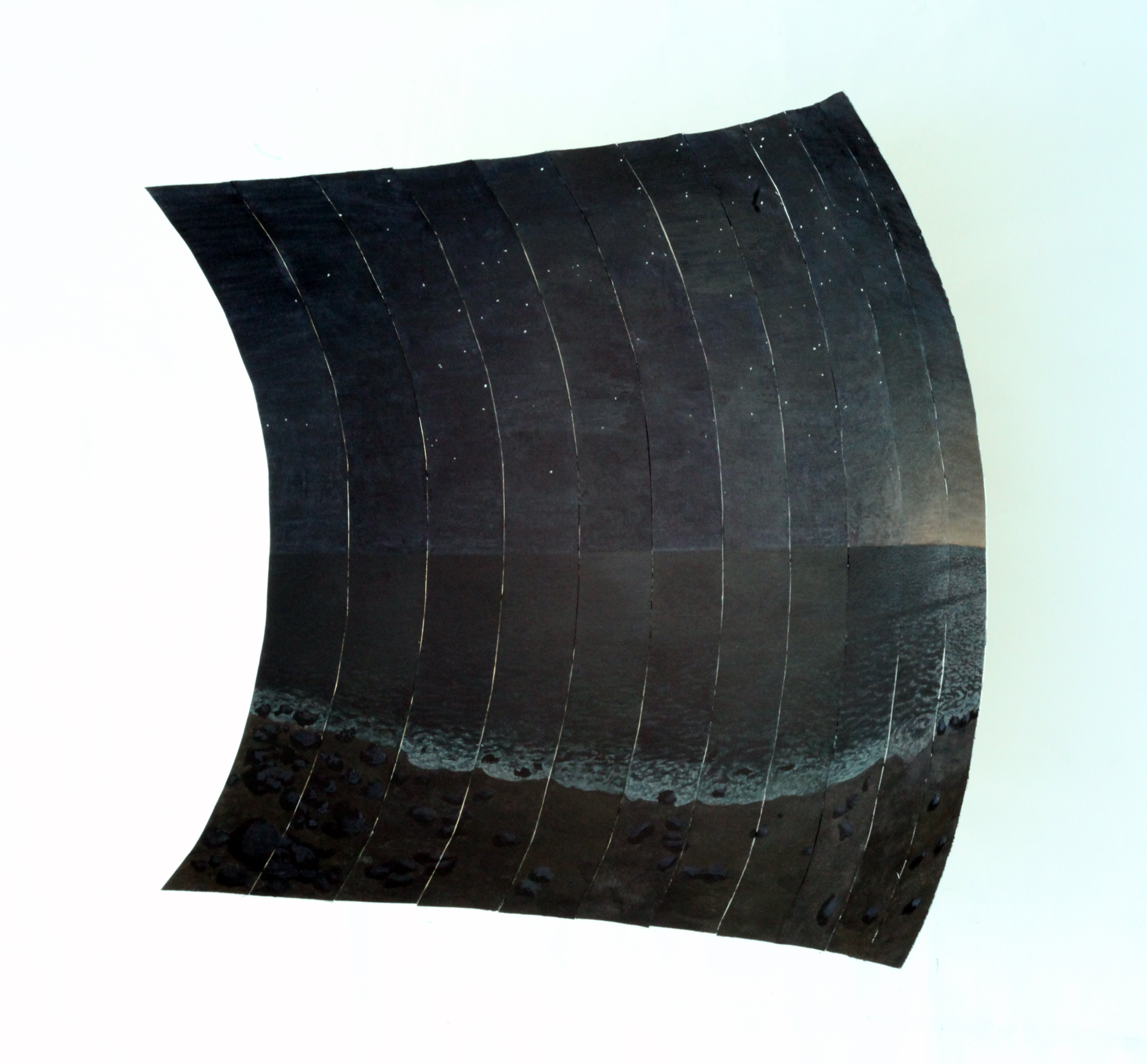

From line (the primary focus of their practice back in those days) (only two years ago) to color, all as a way of getting at the true experience of "the volumes of light that fill the world," as they say. Which made the invitation from the good people at CUE all the more irresistible: did I have any thoughts on someone I'd like to see exhibited? Did I ever!

I went over to their studio again the other day and in addition to getting my first good look at some of their most recent concave work (the watercolors of nighttime ocean horizons; the swirling colored-marker elaborations of atmospheric perspective), and a fresh infusion of more of their proliferating insights (the contention, for example, that light itself as it bounces off surfaces is always matte and never shiny, our brains only fool us into thinking it's shiny, which is one reason the watercolors finally weren't working as the closest possible approximations of what it is to see), I got to see several of Ryan's recent sumptuous blue-field rice-paper banners, and also, dangling from a thread hanging from the ceiling, one of Trevor's latest green and orange pipecleaner constructions (another of his models of the operations of light and sight). Trevor related how a girl had been over the other day and, captivated by the pipecleaner matrix, hushed to silence, eventually declared, "It's like the secret of the universe."

"Yes!" he recalled exulting. "That's exactly what I was going for!"

At which point, once again, they cracked up, laughing.

View CATALOGUE

YOUNG ART CRITICS: Deenah Vollmer on Ryan and Trevor Oakes