Mike Metz

Curated by Joseph Masheck

December 8, 2012 - January 26, 2013

Opening reception: Saturday, December 8, 6-8pm

Mike Metz lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He has exhibited in the United States and internationally. Installations include Snared-trapped and concealed, T-space, Rhinebeck, NY, 2011; Venice Wall, (What is intellect?), at the 52nd Venice Biennale, curated by Gavin Wade, Venice, Italy, 2007; City Art: New York's Percent for Art Program, The Center for Architecture, New York, NY, 2005; Strike, curated by Gavin Wade, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, London, England, 2002; In the Midst of Things, curated by Gavin Wade, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, England, 1999; Letter S Road: Re-marks on Site, Art Omi, Columbia County, NY, 1992; Bunker / Beacon, The Kitchen, New York, NY, 1974; Trying to hit the mark, 112 Greene Street Gallery, New York, NY, 1971; Blueprint for Performance/Extended but Camouflaged, Albright Knox Museum, Buffalo, NY, 1971. This marks his first solo exhibition in New York City since 1995.

Joseph Masheck, art historian and critic, has published twelve books, most recently The Carpet Paradigm: Integral Flatness from Decorative to Fine Art (New York: Edgewise, 2010), Le Paradigme du tapis, trans. Jacques Soulillou, ed. Marc Dachy (Geneva: Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, 2011), and Texts on (Texts on) Art (New York: The Brooklyn Rail, 2011). A new work on Adolf Loos is in production at I. B. Tauris (London). A former Guggenheim fellow, Centenary Fellow of Edinburgh College of Art (University of Edinburgh), and recent Visiting Fellow at Cambridge University, Masheck was the first American to receive a grant from the Malevich Society. He has served as editor-in-chief of Artforum(1977-80), a columnist at the Boston Review (1985-87), a contributing editor of Art in America (1987-2012), on the advisory board of Annals of Scholarship (since 1998), a consulting editor of the Brooklyn Rail (since 2004), on the advisory board of Art in Translation (Berg Publishers, Oxford, on-line; since 2009), and as of 2012, and editorial consultant of the reviving New Observations.

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

For most of my life I have been creating language-based volumetric forms that have multiple interpreations, in order to let the mind move from one possibility to another and back again, unable to confirm one view as more correct than another, ending with any recognition as misdirection, overflowing with referents or referrals.

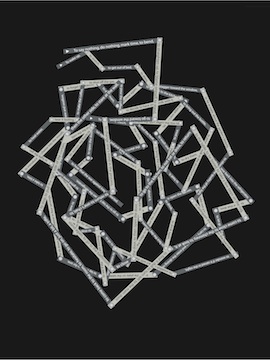

Typically, these objects are made of two or more parts where each part -- both alone or when combined -- form the verbal visual connections that allow significance. These objects use various materials including bronze, aluminum, copper, steel, sheet metal, cement, styrofoam, soap, and vinyl. The banners use canvas, paper, or vinyl.

I seem though to need to start with a drawing which approximates an obliquely recognizable object where the affinities between that object and its names form the details of a potential story or discourse. This is done by way of needing to nail the names to the object -- attempting to make the name and object real. In some cases, this take is actually inscribed over the object's surface with path-like text, forming the shape of the object. In addition, the returning and reworking of an inscribed drawing as a way to spend ones days is finally what is central to the making.

CURATOR'S STATEMENT

Mike Metz and I probably belong to the only generation that, confronted by the famous exemplar of imagic ambiguity, can answer the question of what one is looking at by saying, "The duck-rabbit illusion." Before us, people were too unsteady with images to be more than fascinated or flustered by something's one moment seeming to represent a duck and the next a rabbit; today, I have to wonder if most kids could even discuss actual ducks and rabbits. While Metz has a diverse artistic practice, making objects with ambivalent or multivalent concept-identities is typical of his work, and telling. It is easy enough to call him linguistic and class him as conceptual; but what will it mean to say so?

In 'Mike Metz as a Brand of Sculpture' (Arts Magazine, January 1991) I entertained the notion that his work does not consist of a merely representational play of concretized nouns (e. g., 'duck,' 'rabbit'), like three-dimensional puns, but that extending over the play of nominal or noun-like object identities comprised an artistic identity not marked logotypically, like mere churned-out products, but more like a styled brand. I shall draw an art-historical parallel, after making an unfashionable point: that art, qua art, is not communication. Why complicate matters just when it would be so easy to reintroduce Mike as a computer hotshot who studied and taught graphic design, which everybody seems happy to consider communication? Because something important is at stake: the answer to Nelson Goodman's question, inLanguages of Art (1968), of what artistic "symbolization" is really up to if not communication, namely: "cognition in and for itself."

The most objective-sculptural pieces, along, ironically, with the more discursively textual rather than rebus-like works, show that Metz know that puns aren't poetry. Having two or more 'things' cancel one another by coexistence in material extent and space makes at once for abstraction and linguistic concreteness (something similar happens where texts snap in and out of black-on-white and white-on-black). One such piece, the big Rabbit / Candle-flame / Spoon, 1992, of sheet copper, has sufficient formal identity to resemble a certain lost wooden Construction from 1920 by Aleksander Rodchenko, with paired bars that, in rising, broadened, then narrowed and crossed. To it Rodchenko attached letters to serve as a caption-title in a Dziga Vertov newsreel of 1922 - which wasn't just doing communications either: it made for more cognitive play, in Goodman's sense, than the newsreel required as documentary communication. For another Vertov newsreel title Rodchenko used noodly white-against-black letters, askew, quite like Metz's similarly bent-pipe lettering; for example: Double Portrait (for Dorothy Day), II.

Only lately have I seen even Metz's longtime play with object-shapes adumbrated in Rodchenko's early modernist compositional "atoms," in his word, with nicknames of sorts, such as "scissors" for an 'X'-form or "accordion" for a zigzag. More than the Minimalists in their general relation to Russian constructivism, the linguistic Metz can also be seen to share the heft and bolted stiffness of Rodchenko, with the art-historical connection in turn underwriting "cognition in and for itself."

View CATALOGUE

YOUNG ART CRITICS: Harry J. Weil on Mike Metz