Carrie Olson

Curated by Natalie Marsh

January 21 – March 13, 2010

Carrie Olson was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. She moved frequently while growing up and ended up settling in London, England for several years before moving back to the states to enroll in art school. She received her BFA from Massachusetts College of Art in Boston in 1996 and her MFA from the University of Colorado, Boulder in 2001. She has exhibited in group and solo shows throughout the United States and internationally. Her most recent solo exhibitions include the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art, Grand Rapids, MI, 2009; the College of Wooster Art Museum, Wooster, OH, 2008; and the Zentrum Für Keramik, Berlin Germany, 2008. She is currently an assistant professor of Studio Art at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. Olson's exhibition at CUE Art Foundation marks her first solo show in New York.

Natalie Marsh is an artist and curator working across numerous disciplines and media. She holds an MFA in painting and PhD in Asian art history from The Ohio State University. For five years she served as the founding Director of Exhibitions at Columbus College of Art & Design in Columbus, Ohio. Since 2007 she has been the Director of a new museum established at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. The museum encourages the research, exhibition and care of its 8,000 objects, including one of the largest collections of Burmese art and artifacts in the country and a strong collection of American and European works on paper, and to bring compelling contemporary art and visual culture to University and regional audiences. Her current research and writing stretches from contemporary transnational South Asian media, religion and technology, to Western art and visual culture. In addition to researching and curating, she teaches a range of subjects at the University, reflecting her dual background in studio art and art history/visual culture and her commitment to liberal education.

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

I am interested in the role objects play in our lives - the status we assign them and what that communicates about our identity, be it personal or societal. While this is an ongoing theme in my work, over the past few years I have also been quite focused on fear - what provokes it, how we process it and how it can be manipulated. It seems this past decade has been defined by a carefully choreographed dance dominated by consumption and fear; a dance in which the majority of the population participates.

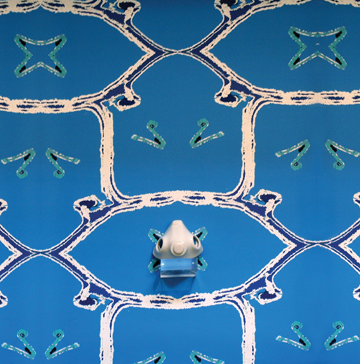

The work in this exhibition centers on porcelain respirators that I have cast from molds of half-face respirators. Their material (Limogés porcelain) speaks of ornament, collectability and status, but their form implies a very specific utility. These respirators act as a vehicle for exploring how changes in cultural context make an object more valuable. The run on duct tape and respirators after 9-11 and the ubiquitous sight of dust masks in Hong Kong and Toronto during the SARS scare and once again this year with the swine flu, are recent examples of how quickly an object's value can shift in the culture.

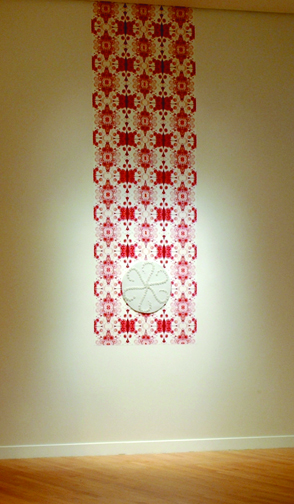

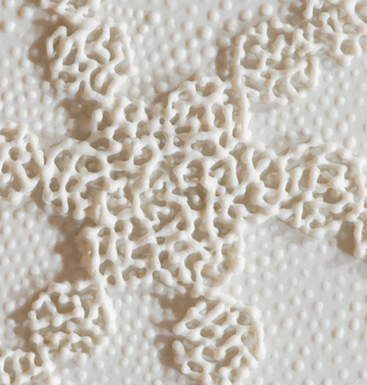

Surrounding these respirators is a "spectacle" comprised of large digital prints and hand carved porcelain disks. The images on the disks and prints are created from microscopic photographs of virulent organisms that I digitally replicate, alter and arrange into patterns. The disks are round like a Petri dish and many of the patterns are inspired by Busby Berkeley's choreography. These types of elaborate dance routines were very tightly choreographed to create purely ornamental human formations, where the individual is important only as a component of the composition. I exploit the role of ornament as mediator; it is the system through which the content of the work is both constructed and filtered. Specifically, I draw on the transformative nature of ornament as a device to examine the complexities of identity construction in contemporary culture.

CURATOR'S STATEMENT

In 1982, Thomas McEvilley wrote of the hold that Clement Greenberg's formalism exerted on the discourse of 20th century art: "Passionate belief systems pass through cultures like disease epidemics." McEvilley's declaration raises intriguing concerns when considering the most recent work of ceramicist Carrie Olson.

Situated in the simultaneously epistemologically delicate yet powerfully subtle sites between Greenbergian distinctions of pure form and illustrative content, potentially neither, potentially either, productively both, ornament may be located along a visually and conceptually sweeping continuum. Carrie Olson's patterned multi-media installations insist at first that we allow ourselves to be absorbed by her insidiously alluring "flora" ornamentations but then "dis-ease" sets in when we find Olson assigns signification-motivating diagnostic titles, Marburg Galliard, H5N1 Cakewalk, the double evocations of disease and folk dance. Her digitally manipulated wallpapers illustrate, in the arbitrary representational sense, the forms of myriad microscopic microbes and viruses. She surrounds us with their vibrant and somehow comforting repeating structure. Yet, disorientation is articulated through the wallpaper's literal shortfall; it does not reach the floor and hangs like a dubious standard. Floating like treasured porcelain heirloom plates atop these "banners" are low relief disks disguising their dangerous petri-dish inhabitants who dance harmless "waltzes." These "follies," as Olson aptly describes them, suggest the nature of parallel cultural constructions: fear and the soothing market-ready domestic arsenal to conceal and control it.

The continuum along which Olson's works travel is twisted and turned upon itself, like a Mobius strip upon which form and content exert inseparable and indistinguishable identities. This challenges Greenberg, who asserted, "The avant-garde poet or artist sought to maintain a high level of his art by both narrowing and raising it to the expressions of an absolute...‘Art for art's sake' and ‘pure poetry' appeared, and subject matter or content became something to be avoided like the plague." Olson's work is an ironic redrawing of Greenberg's autonomous art; it literally represents disease and plague embodied in exquisite form. Her content is her form. Olson's work thus also grapples with the overarching concerns of late 20th century ceramic art discourse that have both polarized and ghettoized ceramics and ceramic artists for decades: does form trump function, and does art trump craft? Olson cleverly bypasses this discourse in the intimately interconnected content and form of her imagery of the paradoxes of contemporary life.

Olson does not deal in absolutes; her work is deeply imbricated with layers of manipulated and intertwining meanings, with both formal and conceptual implications, that reflect 21st century existence. Wryly, she asks us to passionately breathe through the false logic of insufficient cotton masks, and reminds us that propaganda still works even if we know its languages.

View CATALOGUE

YOUNG ART CRITICS: Christopher A. Yates on Carrie Olson