Art Green

Curated by Jim Nutt

February 5 - March 28, 2009.

Art Green was born in Frankfort, Indiana in 1941. His mother was a natural colorist and gardener, who learned to piece quilts as a girl in Alabama. His father was a civil engineer, who worked for the Nickel Plate Road.

His work was profoundly influenced by the artists and teachers he met during his studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as by living in that city in the 1960’s - a time and place of great contrasts and competing ideas. After he graduated, he joined five other recent Art Institute graduates for the first of a series of group exhibitions called the Hairy Who. In 1969, he accepted a teaching position at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Nova Scotia and that same year he married Natalie Novotny, an Art Institute graduate in pattern and fabric design, who influenced the subsequent appearance of patterned overlays in his work. They eventually settled in Ontario, Canada where he taught at the University of Waterloo from 1977 to 2006.

Some of his recent shows include a 2005 retrospective at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery, Kitchener, Ontario; a two-person show (with Suellen Rocca) at Chicago’s Corbett vs. Dempsey Gallery in 2007 and a solo show at the Stride Gallery in Calgary, Alberta in 2008. His work is included in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, The Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario and the Museum Moderner Kunst in Vienna, Austria. Green’s exhibition at CUE marks his first solo show in New York since 1981.

Jim Nutt graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL in 1965. He first came to prominence in 1966 as one of The Hairy Who, a group of six Art Institute alumnae (Jim Falconer, Art Green, Suellen Rocca, Gladys Nilsson and Karl Wirsum) who exhibited together on the south side of Chicago at the Hyde Park Art Center. He and his wife, Gladys Nilsson, moved to Sacramento, CA in 1968 where he taught for seven years at Sacramento State College, returning to the Chicago area where he continues to live and work. Among the shows he participated in at the time were Human Concern/ Personal Torment at the Whitney Museum, New York, NY in 1969 and the Venice Biennale, Italy in 1972. The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago gave him a one man show in 1974 which travelled to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY. More recent shows includeEye Infection at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam in 2001, Disparities and Deformations: Our Grotesqueat Site Santa Fe Biennial, NM in 2005 and Gossolalia: Languages of Drawing at Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY in 2008. He is represented by David Nolan Gallery, New York, NY.

ARTIST'S STATEMENT

I am still surprised (but no longer much upset) by the fact that a pencil held at arms length will cover the full moon – and I once saw a child turn to her mother from a hundred feet away and scream "Mommy – how did you get so small?"

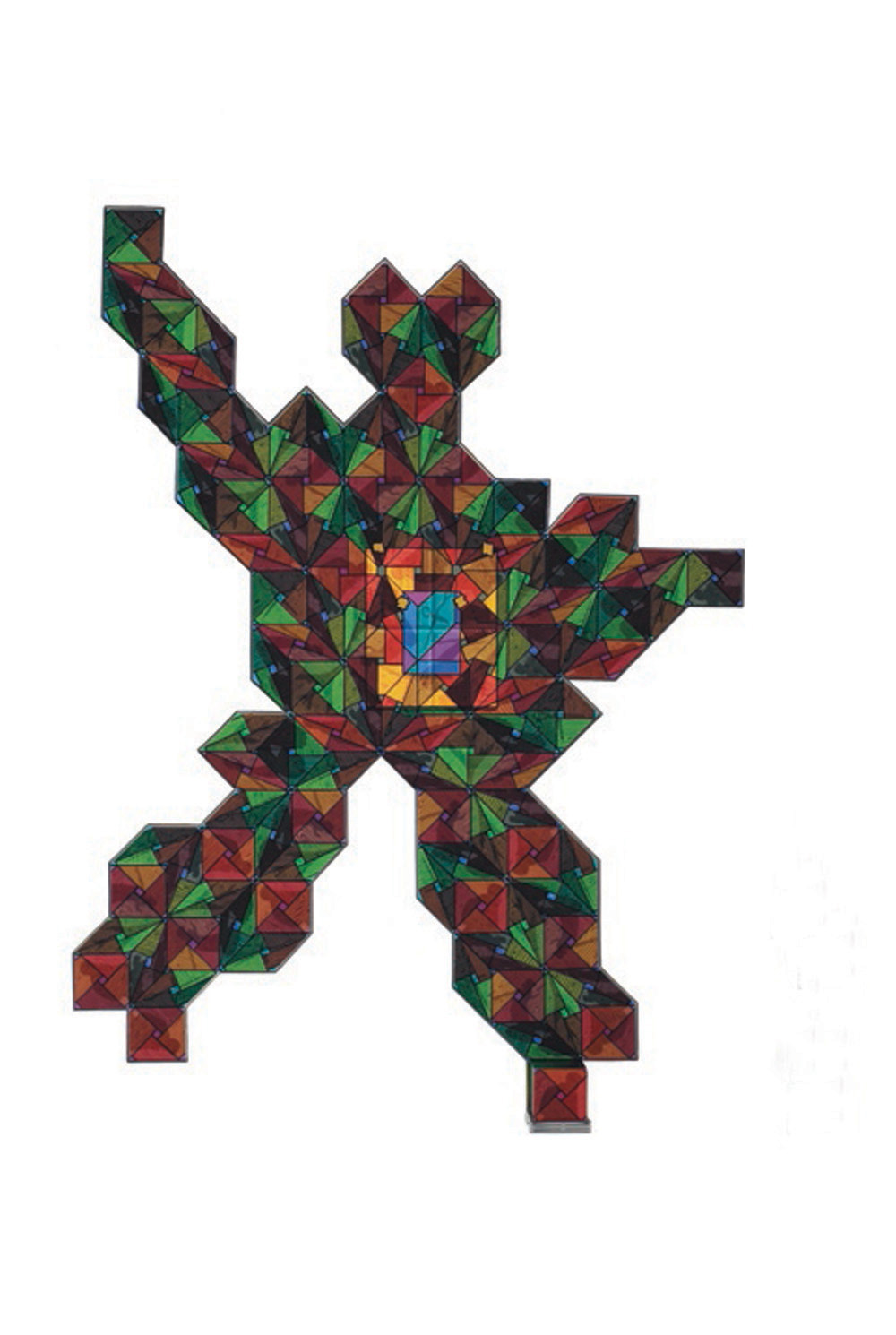

Although I assume that linear perspective was invented to regulate such mysteries, I have more often used it to create further ambiguity. My recent work had its beginnings in the mid -1980’s, when I first got interested in trying to simultaneously represent all six sides of a cube. I painted a set of blocks that could be re-arranged to make six different pictures. To experience the whole thing, I had to put together each separate image sequentially and hold the others in my mind – I could only view one side at a time.

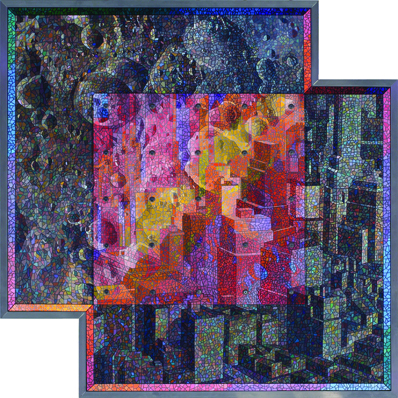

To overcome all this, in my 1987 painting Blockbuster, I opened up and flattened out an image-covered block. Then, by connecting sides to adjacent sides, I tiled them all out to form a pattern that contains the block from many possible viewpoints. I did the painting Near Miss, so I could overlay a turning transparent cube through a cycle of all of its views. In these works and others I have used isometric cubes of the sort that are sometimes used in quilts – the ones you can equally look up at, or down upon, at will.

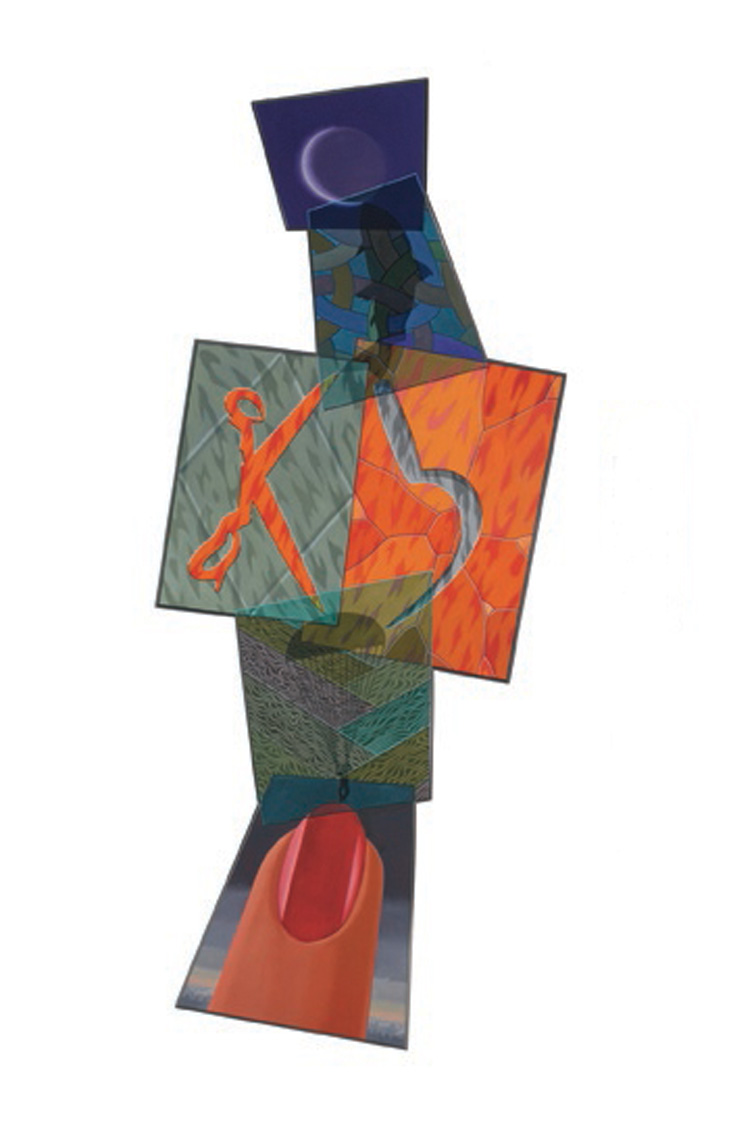

My most recent paintings include towers of dubiously balanced images that were inspired by seeing amateur snapshots that accidentally juxtaposed near and far in unlikely ways. My childhood taught me that things in the air tend to return to earth. Supporting some distant object with the tip of a fingernail is improbable, but it still seems like the right thing to do.

Being strongly of two minds about many things, I aim to make paintings that can support contrasting interpretations. I layer contradictory images and patterns in my work for that purpose, so that the viewer can see first one aspect, then another – but rarely both together. I hope that my paintings encourage such selective viewing, necessarily carried out over a period of time.

My work starts as a shifting pile of tracing paper drawings, and it generally takes me a few months to develop that into a completed painting. By then, I know so much about it that I can’t see the painting as others might; I simply see what I already know. After time has passed, looking at it again, I sometimes feel that I’m trying to follow the frail thread of a dream back to its beginning.

CURATOR'S STATEMENT

by Jim Nutt

I was struggling in a first year painting class, desperate to do anything that looked better than half baked, when I became aware of some movement behind me at the back of the room. Though the interlopers were unknown to me, I slowly became fascinated with the distraction. They were silently removing a painting from the storage rack, giving it close scrutiny, and with the aid of animated gestures, argued in hushed tones the vices and virtues of every square inch of the painting at hand. And there was some giggling. I had never seen such a lengthy and animated examination of a painting. Needless to say I was impressed and hoped to make their acquaintance at some point. Fortunately I did, eventually discovering they were fellow first year students Cynthia Carlson and Art Green.

As I came to know Art, I realized how common this sort of behavior was for him. When he became interested in something, say an image or idea or their relationship, he would follow the interest wherever it went. Invariably, his progress would begin to double back on itself, and he would then find himself proceeding in the opposite direction. Then on to a variant, and then another and so on. It wasn’t exactly willy-nilly, though at times it appeared so. Open ended investigation of this sort quite often leads to a state of confusion in most of us, but for Art it leads to possibilities, often to multiple paintings, each nailing one or another destination. It is not surprising he would become fascinated with the potential of the oscillating illusion of necker cubes or find time to ponder if it is better or worse that a rolling stone gathers no moss.

Curiously his paintings are simultaneously both easy and difficult to look at. At first glance, there is a firmness of purpose and legibility of means that suggests casual grasp is possible. They seem to be and then are easy to read, encouraging a closer look. But this leads to my realization that something’s not quite right, but then it is. I have left easy-read and am now in the painting.

I experience this every morning when, half awake as I meander down the stairs, I find myself slipping into a new part of his painting which hangs on the wall at the foot of the stairs. I may experience the painting whole for a moment, but before I can help it, I‘m in, traveling yet another previously unnoticed path. What a treat!

CATALOGUE ESSAY Meghan Bissonnette on Art Green

VIEW CATALOGUE