This essay was written in conjunction with Country, Home, on view at CUE September 5-October 10, 2015.

Migrations create lacunae. They cause erasures. They occur for reasons that are obvious and obfuscated in equal measure. They ensnare people in webs of unfamiliar language and trauma, forcing engagement with unknown rules and routines. They scrub the lived histories off of people on their way from one nationality to another. Migration has a way of twisting specificity from stories, removing the details, like a wet cloth expels a liquid. Yet art is capable of expressing this loss; it can untwist the cloth. It is able to show us what we cannot say in a glance or an extended stare, a breath, a tube of color, a thread, a photograph of light from years ago. It can make present histories that are difficult to manifest. There is, in short, a volubility in art that gives shape to the erasures caused by human migrations.

“Country, Home” is a phrase that can be turned over endlessly, dialogically, in the mind: Does it refer to a place or a structure? Someone’s home country, or their country home? A state of mind or a nation state? There is a difference between country and home, but each shifts what it means to reside in the other. Every country has its idea of home, and each home expresses unspoken attributes of its country.

I think about how the Chilean-born artist Rodrigo Valenzuela in Here, a three-minute video piece, starts by showing us a black and white scene of a mottled, lifeless desert, and just as we settle into the splotchy, dry view, we notice seams along the image, and then it slowly begins to move, to slide away, to pan out. A finger ekes into the frame from the lower right corner, pointing, or appearing to point, first at a rock. The camera continues its slow retraction, gradually pulling back to reveal an endlessly broad desert valley dotted with scrub. Perhaps the finger simply points into the valley? There are ambient sounds, the sounds of straining wood, pockets of silence, then a snapping tree. The finger hangs like a didactic gesture toward an ill-advised, difficult, or unavoidable route, suggesting no alternative. But it is also submissive, like the arrow of a weathervane helplessly acknowledging the direction of the wind as the camera makes its slow shift.

There’s a circularity in Here that resonates with this exhibition’s title, a flickering engagement with one’s sense of purpose, danger, tranquility, the past. One drifts into the image and away from it as the creeping movement of the camera elongates time into something contemplative, a meditation. The movement—in a sense, a form of migration?—creates a border, then drains it of its power by pulling away from it. One watches time pass inside this frame on a discontinuous course from the present. This is not Frost’s path diverging in a wood, or even Borges’s garden of forking paths. The image continues its slow creep, zooming out. Just over a minute into Valenzuela’s video, we reach another border, a transition from grayscale into color. What we’ve seen until now is a photographic image, composed of tiled squares; we now learn that the image is mounted on a structure set in the middle of a lush forest. The site where the camera physically sits is the rain-soaked opposite of the black and white desert. The camera continues to slowly widen its field of view, creating a sensation that the forest is enveloping the photograph of the desert, reducing it to an image lost in the wilderness, with a man in a black shirt pointing into it, into a superficial, monochromatic version of some other nature, some past time, a harsher climate.

The slow-pan out calls to mind similar shots in everything from Kanye West’s Power or FKA Twigs’s Two Weeks music videos to David Attenborough nature documentaries. Its power lies in its focused slowness which feels in some way analogous to staring into a fresco: the slow, constant movement destabilizes geometry through motion, relieving the eye of its need to dart around. The point of view in Here is, in a way, like the one seen from the vantage point of Walter Benjamin’s angel of history. It focuses, then widens to accompany what literally becomes a “bigger picture” even as it remains the same size, and we remain outside of it.

This work, linking two worlds as seen from a third, colliding media into one another reveals the pervasiveness of borders. The relationship between borders and framing, how they tilt your world and determine your view; how frames determine what gets seen and how we see it; that framing determines kinds of power, and it is always there as a way of leaving people out, selectively forgetting; that borders are limits that structure how we relate to the social and the natural worlds; that we have no real sense of things from inside them.

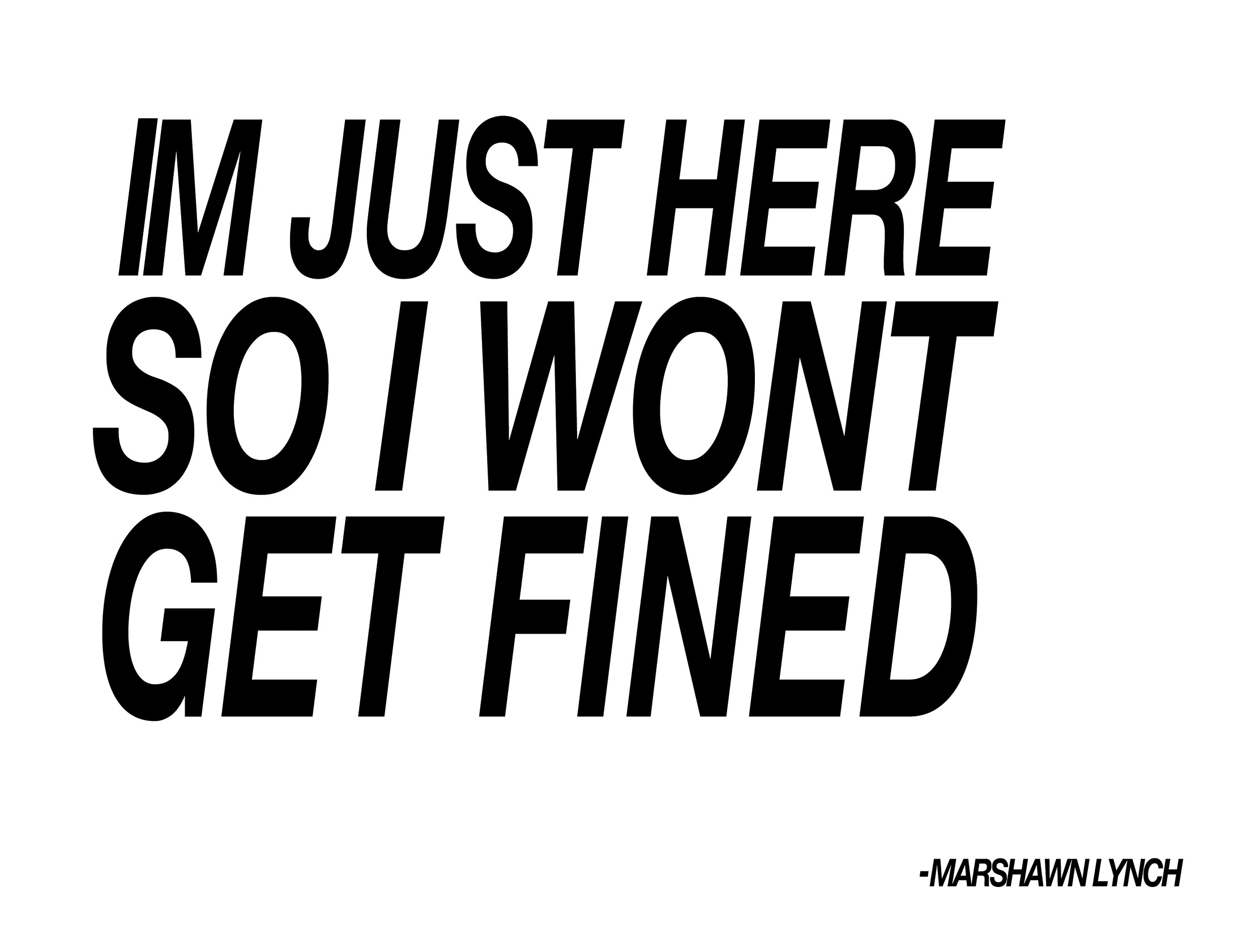

Marshawn & awn & awn, a sparse, layered, five-minute sound piece by Lagos-born artist chukwumaa, addresses the “negation, refusal and defiance” of NFL player Marshawn Lynch within “spaces that function to alienate or control”—like post-game press conferences, where Lynch famously shuts down journalists eager for insight by not responding to their questions. Alienation and control figure into spaces where there are interactions and transitions between different powers, as, for example, at an airport. The piece begins with a pulsing sound. There’s a voice that drifts through it. The pulsing repetition and the words put us in a place between speech and music. There are singular notes of indeterminate origin, sounding in silence. “I’m just here so I don’t get fined,” the voice says, reverberating, shifting, sounding so familiar, it repeats. Did it say ‘fined’ or ‘fired?’ What’s the difference? The valence of the phrase, its force, lands differently each time. Apologetic, flippant, confrontational, serene. “I’m just here so I don’t get fined.” The repetition writes and rewrites what’s said. The pulsing in the background, meanwhile, crosses a border and becomes musical. It starts somewhere high and falls lower, manifesting a beat, the pulsation becomes rhythm. My mind drifts to the incantatory quality of Steve Reich’s “It’s gonna rain,” except instead of a preacher’s admonitions, we have a hero’s refusal. Fresh off the battlefield and Marshawn just doesn’t fucking want to talk to you guys, sorry. Our journalists are so hungry for controversy, how can we blame him? Where Reich’s composition becomes generative, chukwumaa’s remains focused like a razor on this refusal. His heart is unquestionably in the game, but he is not here for this circus, not here to be brandished by others as the hero, to be poked and questioned. That he does it coming off as such a savvy navigator of the politics of appearing in contractual spaces reveals how someone’s small slight can become an act of radicality, a rightful claim to agency and self-determination.

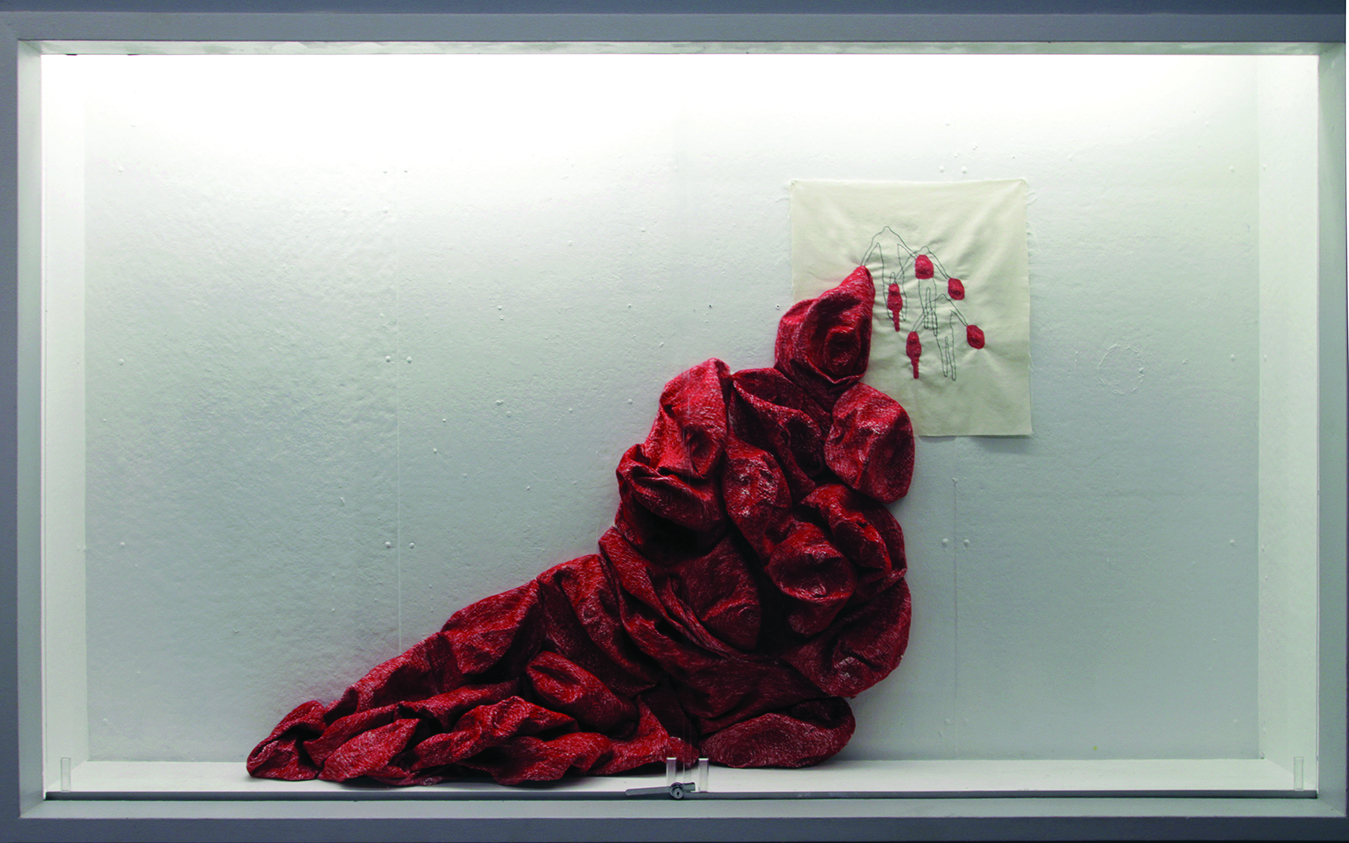

Alejandra Regalado’s documentary project, “In Reference To: Mexican Women of the U.S.,” pairs portraits of migrants from Mexico to the U.S. with photos of objects they chose to bring with them on their journeys. It’s the kind of journey that Regalado, a Mexican artist who now lives in New York, made herself. The diptychs are set against a white background, which lends the portraits a taxonomical, clinical and detached feel. The flat background elevates the objects to totems, quietly recalling Sarah Charlesworth’s “Objects of Desire” series, but oriented less around consumer culture and more around the inexpressible experience of leaving one home forever in order to seek out a more welcoming one in a faraway place. “This is the portrait of my father, whom I never met,” explains one woman of her object, a sepia-toned photograph of a man.

Borders suppress our ability to access material aspects of the past. Regalado’s project acts as a bridge to that past, conveying a sense of loss but also of memory by inviting an open-ended connection between the person in the picture and the thing they chose. Regalado’s work references how, in the course of a long trip, we develop relationships with objects that connect very directly to material aspects of a past, often aspects to which we have lost access.

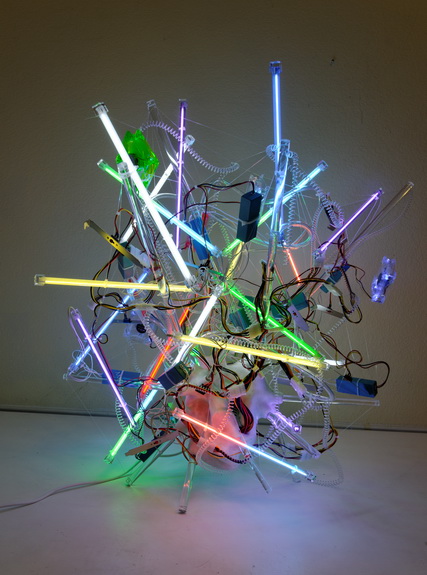

On the other hand, Adela Andea’s sculpture of neon lights and coiled cords, Biopunk Mnemonics, picks up a commercial rather than a personal language. Born in Romania, Andea uses neon tubing abstractly, as a kind of reconfiguration of the meaningless flotsam we encounter in every shop window. It’s as though Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International had been shattered, shrunk, reassembled blind, inflated with argon, and plugged in. The small coils disentangled from the stick-straight tubes of light comprise miniaturized pieces of Tatlin’s tower, but the underlying message seems supranational, pulled from a vocabulary of global consumerism, not assembled as a monument to a kind of progress.

All the pieces in Country, Home make me think about how, while the earliest museums grew out of homes, it hardly meant they were welcoming. It means that, like homes or countries, they relied on certain fixed ideas about ownership and land, membership and belonging, participation and process. In many ways, access was restricted; in many ways it remains so. Interaction between people and property is fenced, regulated and structured. We force what we value into view and shove what we do not out of sight through ignorance, neglect, or omission. We instead settle unthinkingly and complacently into a set of conditions that are usually advantageous to the owners over the viewers. Invitation to these places is often exclusive, rippling lightly through affiliations of kinship that largely exclude those who do not know how to knock on the door.

This essay was written as part of the Young Art Critics Mentoring Program, a partnership between AICA USA (US section of International Association of Art Critics) and CUE, which pairs emerging writers with AICA mentors to produce original essays on a specific exhibiting artist. Please visit aicausa.org for more information on AICA USA, or cueartfoundation.org to learn how to participate in this program. Any quotes are from interviews with the author unless otherwise specified. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior consent from the author. Lilly Wei is AICA’s Coordinator for the program this season. For additional arts-related writing, please visit on-verge.org.

(Young Art Critic writer) Ian Epstein is currently a reporter for New York magazine, where his writing about art and books has appeared in print, online, and in the limited-run Vulture.com art blog, SEEN. He is also an online art editor for n+1. In the past, he has also worked for Hyperallergic, The Nation, Newcity, American Suburb X, and the dual-language photography publication Album, Magazin für Fotografie.

(Young Art Critic mentor) Leigh Anne Miller is the associate editor and picture editor at Art in America. She interviews artists (including Eric Fischl, Marilyn Minter and Keith Edmier) for the magazine’s monthly “Backstory” column, and writes for A.i.A.’s website. She studied art history and Italian at Washington University in St. Louis.