This essay was written in conjunction with Kambui Olujimi: Solastalgia, on view at CUE April 7 – May 12, 2016.

Presently, there is no system that tracks the number of extrajudicial killings of civilians by police officers in this country. There is no annual tally of the victims, no final grand evaluation outlining the who, what, when, or why. There are only approximations and estimates. What we must do then is draw conclusions based on that which is reported and shared publicly. When the smoke clears, we are most often faced with the following scenario: police officer shoots/strangles/chokes unarmed civilian. Perhaps more emphatically, white police officer shoots/strangles/chokes unarmed civilian of color. This was Oscar Grant’s story. This was Tanisha Anderson’s story. This was Eric Garner’s story. What results is a fraught relationship between communities and the very individuals responsible for their safety.

In a city such as New York, this tension is palpable. Black and brown neighborhoods have long voiced disdain towards the “men in blue.” Still, the sustained physical threat of violence at the hands of the state is but one of the ways in which New York City’s most vulnerable suffer. As costs of living rise and wages remain stagnant, poor communities of color must also contend with the consequences of economic travails such as joblessness and dislocation, negotiating the politics of a city in which they continue to be pushed to the outskirts.

This, however, does not necessarily dissuade community members from making attempts to extend the olive branch. Nor should the assumption be made that police officers do not come from or reside in the very neighborhoods that are most threatened. The processes that shape community relations are nothing if not complex.

The works that comprise Kambui Olujimi’s Solastalgia attempt to reckon with the intersections of these phenomena. Olujimi approaches this dialogue from a personal vantage point that humanizes the macro and names the abstract. "Solastalgia" refers to the feeling of dislocation in one’s home environment, where the changes to that environment have rendered it foreign or unrecognizable. Olujimi, who was born and raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, appropriates the term coined by Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht to consider his own emotional response to the changes occurring throughout New York City. Indeed, Olujimi’s work speaks to the shifts that are occurring in an ever stratifying city.

The process of introspection begins with a series of monochromatic ink paintings of the artist’s late mentor and neighbor, Catherine Arline; although such a word does not fully encapsulate the depth of Olujimi’s relationship to a woman he describes knowing “even before birth.” Trusted friend, surrogate mother, grandmother and guardian angel, Arline was the matriarch of Olujimi’s family—chosen or otherwise. Before her passing in October 2014, Arline had served as president of the 81st Precinct Community Council Board for 18 years. She was a Bed-Stuy resident for 65 of them. In this role, she became a critical liaison between youth, families, and elderly community members and local law enforcement. Former NYPD Chief of Department Philip Banks was so close to Arline that he considered her almost a partner, as if she, too, were walking the beat in the 81st. And in a way, she was; so much so that her death brought about an absence that was deeply and immediately felt. For Olujimi, this absence becomes part of the sense of displacement that looms over his evolving relationship to home. With her passing, a layer of intimacy with which Olujimi has always associated with his neighborhood vanishes. So, we bear witness to the mining of grief.

The images of Arline on view in this exhibition are all of her face, and in each drawing she wears a smile that Olujimi describes as characteristic of her warm personality. Arline was acutely aware of the strain between community members and the NYPD and Olujimi has stated she spent much time working to mediate the interactions between the two sides.

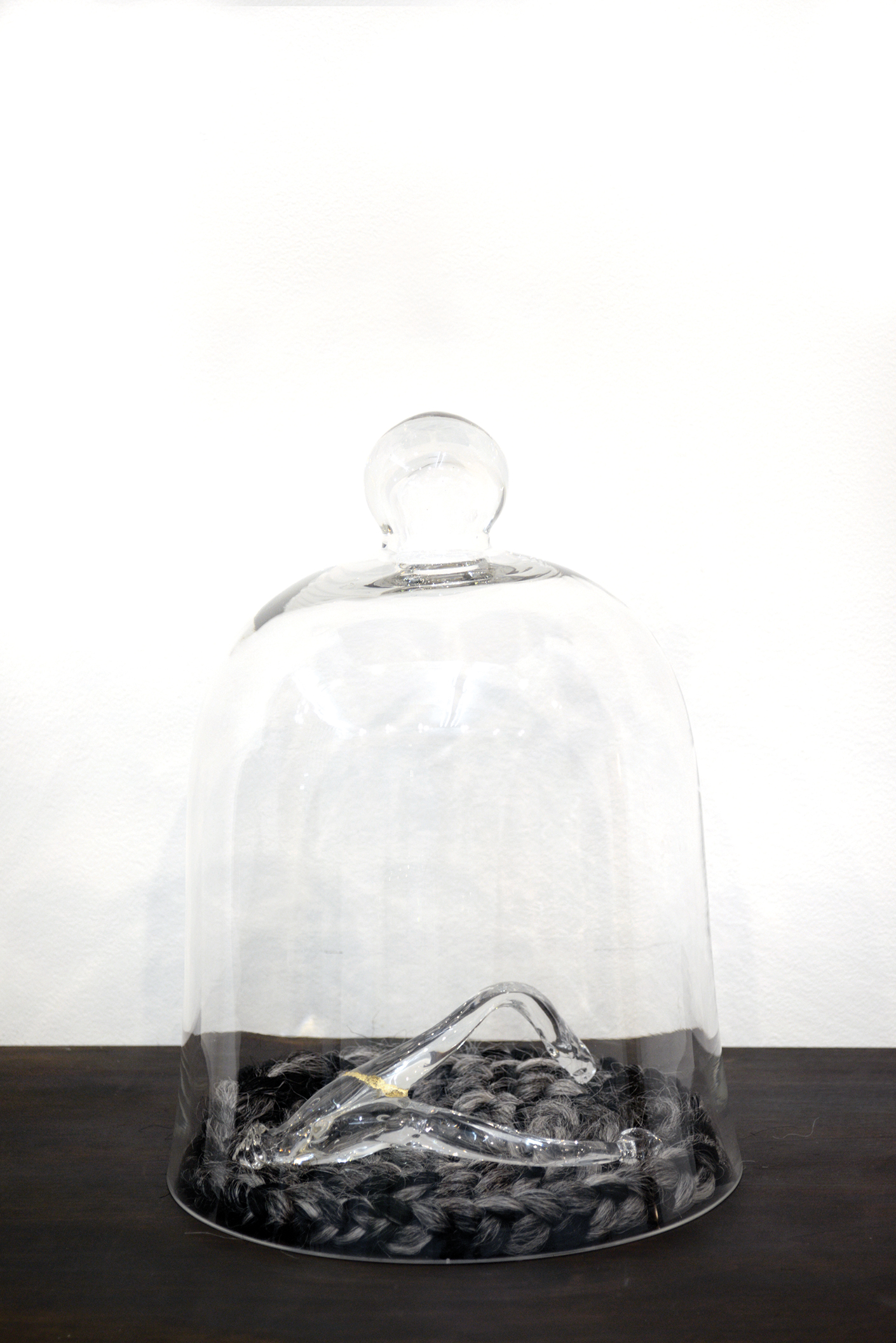

In honor of her life and work, Olujimi has created an installation using pieces of Arline’s furniture and personal objects that bring the private space of the public servant into plain view. Throughout the installation that includes a wardrobe, mounted refurbished doorknobs from Arline’s brownstone, and an old suitcase, we find glass wishbones peppered about. His decision to use the wishbone as a motif suggests that the spirit and work of individuals like Arline as well as a small bit of luck are necessary for reconciliation. Still, as much as Solastalgia depicts Olujimi’s healing from the loss of Arline, it also reflects on how this loss changes the place he calls home.

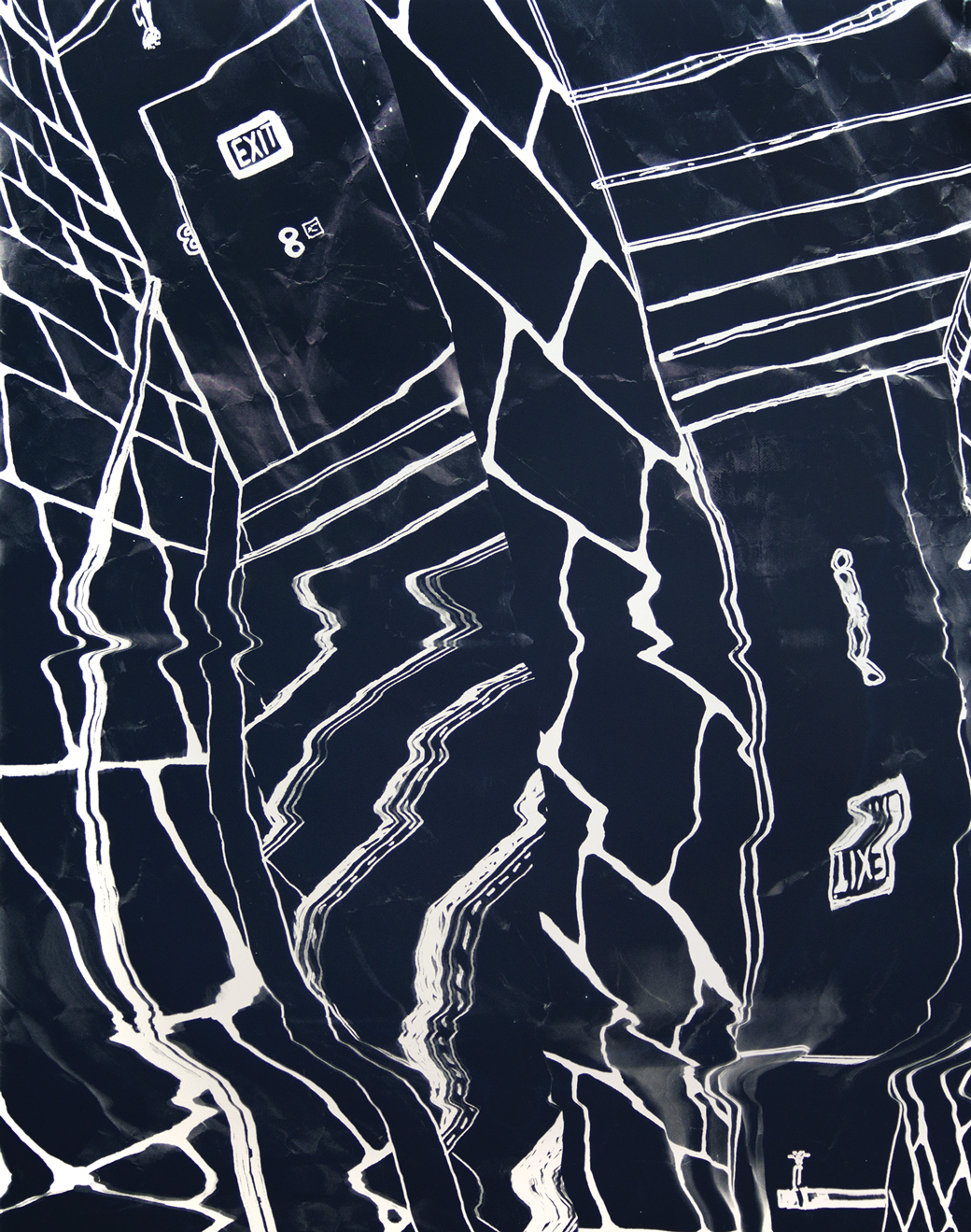

For the viewer must also grapple with the fact that contentious relationships between areas like the artist’s home neighborhood and the police are never easily dissolved, despite the noble work of leaders like Arline. Olujimi’s five distorted silkscreened images of blank autopsy reports and police badges remind the viewer of this truth. Unlike the section of the exhibition devoted to Arline, these silkscreens bear no trace of tenderness. Rather, it is as if the distortions become Olujimi’s way of describing his own complicated, blurred connection to the men in blue as a black man, a way of acknowledging a system that does not operate in his favor. Here we must watch as he confronts the danger.

Yet Olujimi avoids didacticism as he articulates his responses to the changes that surround his life in Bed-Stuy. Instead, the viewer bears witness to the artist’s quiet frustration and heartfelt homage. Though stylistically distinct, each component of the exhibition shares an origin.

Solastalgia emerges from a sense of grief, commemoration, and social commentary. We see these themes explored throughout much of Olujimi’s oeuvre. In Testing, Testing 1,2,3, Testing… (2006), he addresses topics such as colorism in the black community, an intra-racial system of discrimination determined by skin tone. In We Became Statues (2013), Olujimi collaborated with the late Arline in producing a video work in which Arline recounts her time working as a social worker for the New York State Office of Mental Health. Throughout the two-channel video, we listen as she details the grim reality for patients and their families connected to a broken bureaucracy. As her career demonstrates, Arline recognized that she was committed to working within the system in order to challenge its shortcomings.

In the wrong hands, this exhibition might have become an act of navel gazing but Olujimi resists the temptation. Instead, he uses a personal frame of reference to point outward. In other words, Olujimi links the particular with the universal. The tremors of change in New York City are felt by so many albeit to varying degrees and with varying consequences. What are the tools we will use to ensure that such change is beneficial to all of the city’s inhabitants? Solastalgia offers a suggestion: hard work on the part of those working within and outside of the system and, well, a little bit of luck.

This essay was written as part of the Young Art Critic Mentoring Program, a partnership between AICA-USA (US section of International Association of Art Critics) and CUE, which appoints established art critics to serve as mentors for emerging writers. In 2014, CUE joined forces with Art21, combining the Young Art Critic Mentoring Program with the Art21 Magazine Writer-in-Residence initiative. Each writer composes a long-form critical essay on one of CUE’s exhibiting artists for publication in CUE’s exhibition catalogue, which is also published by Art21 in its online magazine. Please visit aicausa.org for more information on AICA-USA, or cueartfoundation.org to learn how to participate in this program. Any quotes are from interviews with the author unless otherwise specified. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior consent from the author. Lilly Wei is AICA’s Coordinator for the program this season. For additional arts-related writing, please visit on-verge.org.

Writer Jessica Lynne is a Brooklyn-based writer and arts administrator. She received her BA in Africana Studies from NYU and has been awarded residencies and fellowships from The Sarah Lawrence College Summer Writers Seminar, Callaloo, and The Center for Book Arts. Jessica contributes to publications such as Art in America, The Art Newspaper, The Brooklyn Rail, Hyperallergic, and Pelican Bomb. She’s co-editor of ARTS.BLACK, a journal of art criticism from Black perspectives, and a founding editor of the now defunct (but still special) Zora Magazine.

Mentor Sara Reisman is the Artistic Director of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, whose mission is focused on art and social justice in New York City. Recently curated exhibitions for the foundation include Mobility and Its Discontents, Between History and the Body, and When Artists Speak Truth, all three presented on The 8th Floor. From 2008 until 2014, Reisman was the director of New York City’s Percent for Art program where she managed more than 100 permanent public art commissions for city funded architectural projects, including artworks by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Mary Mattingly, Tattfoo Tan, and Ohad Meromi, among others for civic sites like libraries, public schools, correctional facilities, streetscapes and parks. She was the 2011 critic-in-residence at Art Omi, and a 2013 Marica Vilcek Curatorial Fellow, awarded by the Foundation for a Civil Society.